Transport and logistics are an integral part of the modular puzzle. Here are the issues you need to keep in mind.

- Without careful planning, the large size of a building module, the need for correct sequencing and the possibility of construction delays can cause unnecessary trouble and expense.

- Getting modules from the factory to the jobsite often means navigating a maze of state and local regulations, all of which affect the schedule and budget.

- Special trailers and cribs are being developed that will reduce expense and material waste, while subjecting modules to less stress during transit.

The logistics of successfully getting modules from factories to jobsites, and of making sure they’re installed correctly, are complex. It’s an important element to consider when planning a new factory and a task that’s best handled by an experienced logistics provider. Unfortunately, this is an area where some manufacturers fall short.

“Hope on Hyde.” The modules were transported from Perris, California to downtown Los Angeles.

Photo credit: Stream

To get a sense of how to create a successful logistics program, we talked with two experts, Carlson Holmquist and Scott Bridger, about the issues that new manufacturers might not anticipate and the problems that inexperienced logistics providers might encounter.

Holmquist is CEO and Co-Founder of Stream Logistics and Stream Modular in Scottsdale, Arizona. Stream Modular is the company’s new division and it’s solely focused on the transportation of mods, pods and panels for the prefab industry.

They cover all of the US and Canada (including Hawaii and Alaska) and have used ferries and barges to deliver to islands off the coast of Washington state and British Columbia, Canada. They don’t own a fleet of trucks, but instead partner with trucking companies.

Scott Bridger is Co-owner and co-founder of ProSet Inc. and ModCribs. ProSet is based in Montrose, Colorado. The company takes care of transportation logistics and installation on larger-scale modular projects. They also don’t own trucks or cranes, but partner with trucking companies and crane companies. They have various set crews, each of which covers a specific geographical region. They recently expanded to cover the whole of the United States, including Alaska and Hawaii.

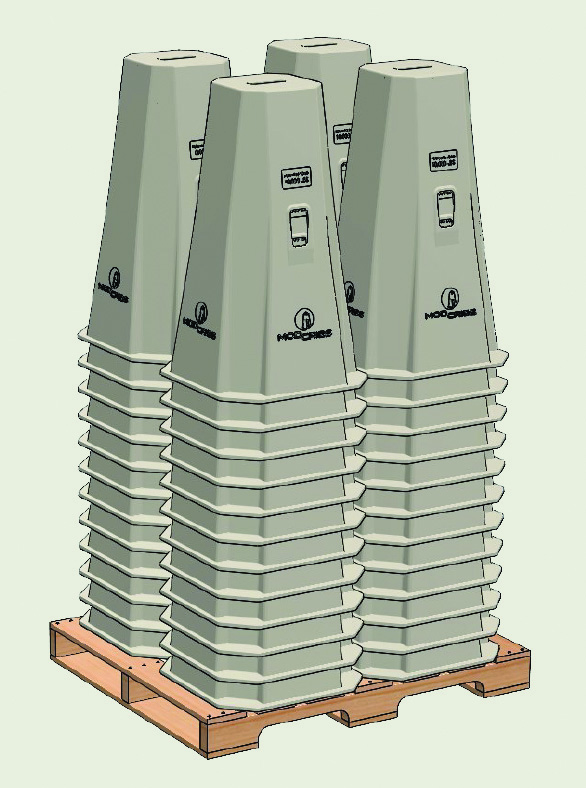

ModCribs was founded this year (2023) to address an easily overlooked element of modular logistics: cribs for the modules to stand on.

Owatonna, Minnesota plant and ProSet installed them.

Photo credit: ProSet

Three Big Challenges

According to Holmquist and Bridger, there are constraints involved in transporting modules that make the logistics more difficult than for most other products. Three big ones are: size, speed and sequence.

Size. This is the most obvious constraint. “The sizes [of a module] determines the route, permits, escorts and the time needed to transport them,” Holmquist says. In addition, the size of the vehicles needed to transport modules can present their own challenges. “Does the site have good truck access? Are there turning radius issues? What is the ingress and egress for an oversized truck?”

Speed. Another constraint is speed. “We want a building erected and dried-in as quickly as possible,” Bridger says. “It’s important to keep the units dry, to prevent any weather infiltration. And the longer it takes to erect a building, the greater the risk of weather damage.” Getting a building erected quickly also keeps costs down. “If we set 12 to 16 modular units in a day, compared to only four to six, that considerably cuts the cost per modular unit for the crane and crews.”

A primary benefit of prefabricated construction is speed to occupancy. “Anything that slows the timeline diminishes that benefit. Our job is to make sure the jobsite never stops or slows because of transportation,” Holmquist says.

Sequencing. Speedy delivery is important for most products, but with modular construction there’s the added need for correct sequencing. It’s absolutely critical.

“Modular units are not interchangeable. Each one has a specific place in the building where it must be installed,” Bridger explains. “When we create a logistics plan for an installation, the first thing we need to know is the set sequence. We work backwards from there.”

To make it less likely that modules arrive on-site in the wrong order, the developer or GC will typically rent a staging yard — usually an empty lot or a parking lot — near the jobsite. Rather than modules being delivered directly to the jobsite from a factory that might be hundreds of miles away, they’re delivered to the staging yard.

The staging yard also helps maintain an even production flow. “We can set 10 or 15 a modules per day, but trucking is usually at a pace of just a few per day,” Bridger says. “That’s another reason we make sure most of the units are already in the local region when we start installation.” Running out of units to set would mean idle crews and cranes waiting for modules to arrive — a wasted expense.

However, while the order of the modules’ arrival at the staging yard isn’t as critical as their arrival at the jobsite, it does matter how the modules are arranged in the yard. “If we need a unit that’s at the back of the yard, and we have to move 10 units to get to the one we need, our efficiency is dramatically decreased,” Bridger says.

To avoid problems, they provide a parking plan for the trucking companies, showing where each module should be parked. The parking plan informs the shipping order, because the first box to ship should be the one farthest in the back of the yard — one of the last modules to be set.

As Bridger puts it, “The set order informs the parking order. The parking order informs the shipping order. And the shipping order informs the manufacturing order.” Ideally, the modules that will be set last will be manufactured first, so trucks can deliver them first.

Photo credit: ProSet

When Sequencing Goes Awry

Of course, things don’t always go as planned. “Say that eight modules were supposed to be set today, but the crew managed only five,” says Holmquist. “Three get pushed to tomorrow, but eight are already scheduled to arrive tomorrow. The delivery and staging of those might need to be adjusted.”

Delays like this can cause pushback from generalized logistics companies, or even trucking companies specializing in oversize loads. They might not have a full appreciation of the time sensitivity of sequencing and may not even know to ask about it.

To maintain good relationships with truck drivers, Holmquist’s company arranges, in advance, a compensation schedule that covers delays. The drivers are warned that things can sometimes get held up (for example because it’s too windy to set modules), but that they will be fairly compensated for any waiting time.

Permits and Police

Permit requirements vary across the US and Canada. Holmquist says, “We’ve compiled all the state data into a centralized database. We can plug in the origin, the destination and the dimensions to get a list of state-by-state requirements.” In different states, different size loads trigger when a permit’s required, when one escort is required, when two escorts are required, or when a police escort is required.

Police might also need to be involved near the jobsite. For example, in tight urban areas it might be necessary to coordinate with the police on road closures.

When a shipment is big enough that a police escort is required, a route survey is usually needed, too. “That’s where someone has to drive the exact intended route and look for obstructions that may not be documented with the Department of Transportation, such as recently started road construction,” Holmquist says. “It’s expensive and time-consuming.”

Holmquist says that “you might look at a map and think it’s only 300 miles, which a driver could easily do in a day. But you don’t know all the constraints there might be along the way. The actual route might be more like 450 miles — because the trucks have to be routed to avoid construction.”

Photo credit: Stream

City Restrictions

Each city also has its own rules, with some being quite restrictive. As an example, Bridger describes a set project in downtown San Francisco, Calif. “The city wouldn’t allow us to close any lanes on Market Street in front of the building. It was a tight urban site with a courthouse on one side and a high-rise on the other. So, the only access point was an alley at the back of the building,” he explains.

However, the building was much too large to set from only one side. “We had one crane in the alley pick up each unit from the truck and put it onto the concrete podium. We had a second crane on the site, closer to Market Street, that set the module on that side of the building.”

And this wasn’t the only complication. The city wouldn’t allow modules to be transported during the day. “The entire set erection of this building had to be done at night, with lights. It was a symphony of complicated nighttime activity.”

Special Equipment: Trailers

The supply of trailers that are appropriate for transporting modules is very limited, “perhaps 5% of the whole US trailer market,” Holmquist says.

The best ones are big enough to handle the weight of the module and also include a built-in hydraulic lifting mechanism. Modules are stored on wooden stands called cribs. The trailer is backed under the module and hydraulics are used to lift it off the cribs.

The alternative is to load and unload with a crane, which is expensive and puts more stress on the module. “[A purpose-built trailer] is a much gentler process than using a crane because the module is fully supported when lifted, rather than potentially swinging and twisting in the air while hanging from a crane,” Holmquist says. It’s also more efficient because just one truck driver can load a module from the factory yard onto the trailer and unload it at the staging yard.

Because there’s a shortage of large hydraulic trailers, compared to the number of factories wanting to use them, Stream is building their own fleet of GPS-tagged trailers and they plan to have 24 by the end of 2023. They will be a big improvement over the standard flatbed.

“A standard trailer is 8 and a half feet wide,” Holmquist explains. “If a module is 16 feet wide, that’s a lot of overhang. It can cause instability and can crack drywall, for example.” Stream’s trailers will have outriggers — extendable arms that stick out the sides — to provide extra support. They will also be able to expand in length to 70 feet.

Photo credit: ModCribs

Special Equipment: Cribs

Although cribs are an essential part of storing and staging modules, they can get overlooked in the planning and budgeting for a project, “especially if it’s a developer’s or general contractor’s first modular project,” Bridger says.

Once modules leave the factory, “manufacturers don’t have much to do with them,” according to Bridger. “It’s not in the manufacturer’s scope to provide cribs at a staging yard that could be hundreds of miles away from their facility.”

The problem is that developers and general contractors don’t have, and don’t want, an inventory of cribs. In most cases, the GC will either have their carpenters build cribs, or will order them from a wood truss company. Because cribs can be expensive to transport or store, however, they often get thrown away after just one job. “Each crib is made of twelve 8 ft. 2×4 studs and 400 nails,” says Bridger. “That amount of resources for such a short lifespan is terribly wasteful.”

Wooden cribs are also heavy — an average 36-inch-tall crib weighs in at 130 pounds or more. They’re a challenge for one person to drag around, never mind lift onto a truck.

Responding to these problems, Bridger’s new company, ModCribs, developed stackable, lightweight cribs made from structural foam. They weigh about 28 pounds each and, because they’re stackable, “600 ModCribs can be loaded onto one truck, and a forklift isn’t needed to load and unload them.”

Although ModCribs will be for sale to manufacturers who want to use them long term, they’ll also be available for short-term rental to developers and GCs, which will be cheaper (and less wasteful) than building cribs from scratch and throwing them away.

Zena Ryder writes about construction and robotics for businesses, magazines, and websites. Find her at zenafreelancewriter.com.