These recent demo homes explore the possibilities and limitations of offsite construction.

Demonstration projects serve an important purpose in the homebuilding world. They allow builders, developers and others to test out new ideas while avoiding many of the risks that come with projects built for actual customers.

Here, we profile three demonstration projects that were on display in the past 12 months. Each explored an aspect of offsite construction. The goal of each was to test new approaches, see what does and doesn’t work, and offer ideas that the industry can use in real projects.

Photo courtesy of DAHLIN

Photo courtesy of PREP Solutions

Urban Infill Ideas

The Picket Fence townhome is a 2,007-square-foot townhome that sits above a 660-square-foot ground-floor apartment with a separate entry. It’s located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania..

A modular home manufactured by Structural Modular Innovations, LLC (SMI), 80% – 90% of the Picket Fence was built in a factory in Strattanville, Pennsylvania, around 70 miles northeast of Pittsburgh.

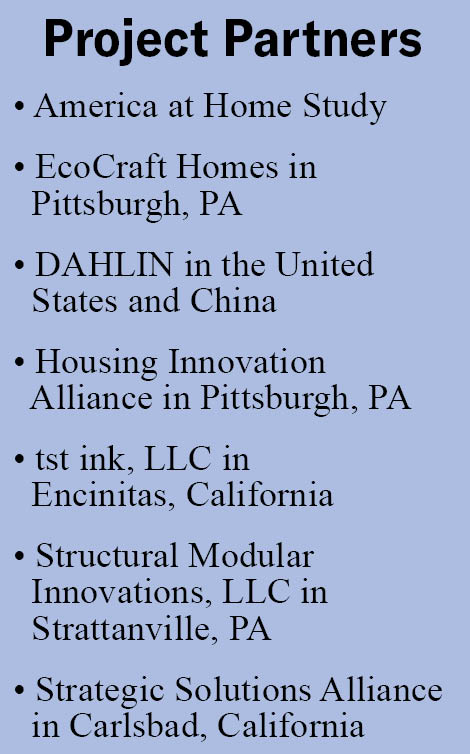

The project was a collaborative effort involving several organizations (see box). Inspiration for its design came from consumer insights gleaned through the America at Home Study, a survey – conducted between April 2020 and October 2022 – of US adults between the ages of 25 and 74 with household incomes of $50,000+/year.

According to Dennis Steigerwalt, President of the Pittsburgh-based Housing Innovation Alliance (the project’s development partner), the name ‘The Picket Fence’ comes from the idea that everybody deserves a picket fence.

Photo courtesy of PREP Solutions

Although the home could appeal to any demographic, it was designed with the ‘Trail Blazers’ segment of the millennial generation in mind, and includes features that should appeal to that group.

The America at Home Study described Trail Blazers as goal-oriented, risk-taking, tech-focused and open-minded. They care about environmental and social issues and seek to influence others. They value health and fitness. Economically, they are relatively affluent, with a median income of $141,000 per year. Thirty-three percent of them rent their homes. They are likely to live with a partner or spouse and may have children.

Like all high-performance homes, this one is an intelligent blend of engineering and architecture. “We created a digital twin of the solution we wanted, starting with… the envelope,” Steigerwalt says. The team “went through a continued optimization exercise to make sure that the core technologies we wanted to include, such as the Rheia comfort system, could be blended with the right investments on the envelope.”

He says that three core goals drove the project. “How do we talk about consumer livability? How do we talk about sustainability for the environment? How do we talk about buildability for the industry? It wasn’t about showcasing a specific product or technology, it was about achieving those results and finding the right technologies to help us succeed.”

Part of the buildability goal was to explore the possibilities of modular construction because of this method’s oft cited benefits of cost-effectiveness and design flexibility.

“We’re trying to break the connotation that a modular home is not attractive [and is] something on a trailer or in a trailer park,” says Ryan White, director of design at DAHLIN, a global architecture, planning and interiors firm and the project’s design partner. The aesthetics “are aligned with what traditionally built homes can achieve.” He does acknowledge that the dimensional constraints imposed by the need for modules to fit on a truck required some creative design solutions.

The sustainability goal was met with a high-efficiency building envelope, high-efficiency heat pump equipment and other innovative design solutions.

There’s a cold-climate air-source heat pump for each unit. The townhome has a Carrier 25VNA4 with a HSPF2 of up to 10.5 and a SEER2 of up to 22.0. The apartment uses a Carrier 38MURA heat pump with a heating season efficiency (HSPF2) of up to 9.8. Cooling efficiency (SEER2) is up to 18 (significantly higher than the 13 SEER minimum requirement for northern states). Each unit includes a Lochinvar electric water heater.

The Picket Fence also features a factory-installed Rheia air-distribution system. Ducts are located within the conditioned space and have fittings that snap and/or twist together without mastic or tape, according to Eric Newhouse, Vice President of Innovation at SMI.

For indoor air quality, each unit is equipped with an energy recovery ventilator and an ActivePure air-purification system. The ActivePure system uses photolysis, a process in which photons break down chemicals to remove contaminants from the air.

Newhouse says that The Picket Fence is designed to meet the specifications of the US Department of Energy’s Zero Energy Ready Home Prescriptive Path.

Photo courtesy of Bing Chen

High-Tech Senior Living

A new demonstration house at the University of Nebraska Omaha campus is designed to test smart technology approaches for housing the rapidly growing population of senior citizens in the United States.

The US Census Bureau counted over 54 million US residents over the age of 65 on July 1, 2019, according to project advisor professor Bing Chen from the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Omaha campus.

Most of the construction of this modular home was done offsite at Metropolitan Community College in Omaha by the college students who are enrolled in trades programs there.

The building will contain a control system that measures energy efficiency, building security, indoor air quality, water collection and distribution — and, perhaps controversially, the occupant’s health. For example, a student capstone project involves creating a radar system to detect whether someone has fallen in the building.

Photo courtesy of Steven J. Eggerling

When asked whether elderly residents might be intimidated by features like voice-controlled household equipment and continual electronic surveillance, Chen did not address the question directly. However, he did say that he is coming from the perspective of a concerned family member — his father has fallen at home several times.

The home’s features include:

- Carrier ductless “Infinity” heat pump

- Rheem hot-water heat pump

- RenewAire air-to-air heat exchanger

- Efficient Alpen windows

- Moen voice-activated shower system

- SEEMRAY high R-value door from Germany

- Nobi fall-detection smart lighting system

- ADA-compatible kitchen and bathroom fixtures

The building has R-50 walls and an R-100 roof with a standing seam metal surface. There’s an 8kW solar array, nearly 30 kWh of battery storage and a backup Cummins generator.

Photo courtesy of Bing Chen

Chen’s team selected the equipment mainly based on quality. The students were working with a grant budget of $150,000. The heat exchanger was donated by RenewAire.

The building of a demonstration home is a real learning process for teams of students and, as part of that learning process, mistakes were made. For instance, the utility room door was placed eight feet above the ground. Also, the electrical layout had to be redesigned after solar experts told the team that they should not have wires running through the rafters.

The costliest mistake had to do with the solar array. “Our solar contractor was enamored with an embedded-panel PV array,” Chen explains. The manufacturer of the array documented that it had been approved by Underwriters’ Laboratory (UL) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). However, Chen said he was told by an inspector that it could not be approved for this type of building.

According to Michael Shonka, owner of Solar Heat and Electric, who worked on this project as a contractor, the problem is due to a 2017 change in the National Electrical Code that requires systems to shut down at the module level with devices located behind the panels. The embedded panels’ disconnect switches were considered inaccessible.

Photo courtesy of Steven J. Eggerling

Fixing the problem required a new roof with an open rack for the panels. “In the interest of getting it done, we opted to remove the roof (first for me in 40 years) and replace it with a standing-seam roof that we could clamp the rack to, so all wiring was above the roof and ‘accessible,’” Shonka says.

Once the building is complete, Chen says, there will be public tours for various organizations such as the American Institute of Architects.

Photo courtesy of Cypress Development

Small Home Ideas

Although builders get lots of flack for balking at innovation, their hesitation is quite rational. Most don’t want the liability — financial, legal, or reputational — of unproven products or systems that can underperform or fail outright. (Ask an EIFs early adopter.)

“The builder’s job is to build homes, not to risk innovation,” says Marianne Cusato, an architect and a professor at the University of Notre Dame School of Architecture.

Cusato is also a partner in Cypress Development Corp., a Panama City, Fla. nonprofit that is focused on innovating small homes. She and the Cypress team gained national repute in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina for designing and building 450 Katrina Cottages in Louisiana. With floor plans starting at 307 square feet, the kit homes were more attractive, more dignified and more livable alternatives to the temporary trailers from FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency).

Photo courtesy of Cypress Development

Katrina cottage kits were even sold by Lowes for a couple of years, but they eventually went dormant because of consumer disinterest and widespread local government opposition to what were essentially accessory dwelling units (ADUs). It was an idea whose time hadn’t come yet.

But Cusato and her partners soldiered on, continuing to look for new innovations. And while they still focus on disaster relief, their wider goal is to develop resilient and systems-built solutions for small homes. The growing popularity of ADUs, along with zoning approval from an increasing number of jurisdictions, makes them optimistic.

That led them to develop what they simply called their Concept Home, which was displayed on the National Mall in DC for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Innovative Housing Showcase last June. The 540 square foot cottage was what Cusato calls “American Vernacular,” with wide eaves and a covered front porch. It was a chance to test some ideas and to get comments from industry pros visiting the Showcase.

One thing they wanted to test with this project was the practicality of steel-framed floor cassettes and wall panels. Cusato insists that, at least in a small and simple home, panelized construction need not mean longer build times. “We arrived at the Mall at the same time as the modular house [that was being displayed] and we kept up with them, even though we were a prototype.”

Another advantage of steel is its moisture resistance: it neither rots nor attracts bugs. That’s important to Cypress, which places high priority on resilient construction. According to Cypress partner Craig Savage, resilience was further improved by sheathing the interior and exterior of the home’s walls with a combination of Windsor One half-lap boards and magnesium oxide structural panels (MgO). The latter offer the strength of OSB but with better water resistance.

After the event, however, the Cypress team concluded that open steel panels aren’t optimal because sheathing, insulation and finishes still need to be installed on-site. “Panels offer design flexibility, but there’s a learning curve with steel, including the need for different fasteners and tools,” says Savage. It’s not a huge deal, but he says it can be a challenge for some crews.

Photo courtesy of Cypress Development

While the partners like steel’s moisture resistance, they’ve decided to try developing a steel-framed structural insulated panel (SIP) that will require less on-site finishing than open panels. It will be sheathed on both sides with MgO board, which can serve as both the structural sheathing and the finish wall surface.

Although a lot of details will need to be worked out, “we think we’re going in the right direction,” says Cusato. “We like the fact that MgO simplifies the building envelope by eliminating layers.”

Photo courtesy of Cypress Development

Cusato and Savage say that they received a lot of helpful feedback during the Showcase. Their ultimate goal is a home that’s engineered to the latest building science principles, that’s simpler to build than a conventional home and that can be completed for an affordable price.

The Concept House has put them closer to that goal but there’s still more to be learned from it. The home will be placed in Panama City as a rental unit and its performance monitored over time.

Kat Friedrich writes about energy, engineering, physics and technology. She is a graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Madison College of Engineering and is the editor in chief of Solar Today. “Small Home Ideas” was contributed by Offsite Builder staff.