Farmers have some things to teach builders and housing manufacturers who want to automate their jobsites and factories

- The challenges faced by agriculture are similar to those faced by construction, yet the agriculture industry has managed to raise its productivity by embracing mechanization.

- Robots are gradually taking over the work of harvesting even the most delicate crops, with different machines and software programs for different species.

- A construction analogy: different trades require different skills and automating them will require trade-specific technologies.

If the building industry wants to remain profitable, it must become substantially more efficient. Construction robots can help automate repetitive tasks, which in turn will improve overall efficiency and productivity. Construction robots take numerous forms and serve a variety of purposes. They range from bricklaying robots and self-driving excavators to robotic arms that assemble housing units in modular, offsite factories.

Builders and housing manufacturers looking to automate usually seek lessons from trailblazers in the construction industry itself. But there is also much to be learned from other industries. One that I believe holds valuable lessons is agriculture.

Both agriculture and construction have gone through transformative phases since the beginning of civilization. They have also faced strong economic pressure in recent years to raise their productivity and keep costs down. However, the difference is that agriculture actually raised its productivity. Today’s farms are a stark contrast to what they were just a few decades ago.

Rise of the Machines

The first step in the automation of farming was the replacement of work animals like oxen and horses with machines like combine harvesters – a transition that started in the 1800s. That transition would be analogous to the homebuilding industry moving from stick-framing to modular construction. The second phase, which is now underway, is the robotization of harvesters and other machines.

The forces that drove farmers to embrace mechanization included demands for higher wages from agricultural workers, limited access to low-wage migrant labor, and increased year-round demand for produce. Many fruits and vegetables can only be harvested within a very small time window, so a lack of available workers at the right time can easily become a huge problem.

Mechanization improved the situation, but today’s farms face greater pressure than ever. With the global population nearing eight billion, there is ever-increasing pressure for fertile land to produce higher crop yields.

One challenge has always been that every crop has a different need. There isn’t a one-machine-fits-all solution. Rather than being intimidated by this fact, the agriculture industry embraced it and created specialized machines for each crop.

While harvesting crops like wheat is fairly easy to mechanize, picking olive trees is trickier. Nowadays, farmers use an olive-harvesting machine that shakes the tree, strips it of fruit and then separates the olives with a pneumatic sorter. Carrot harvesters pull hundreds of plants out of the soil at a time, cut off the tops and drop them back into the fields, while collecting the carrots in a storage tank.

Lettuce is also difficult to harvest manually. Historically, workers spent days bending over and standing up repeatedly, which often caused back problems. Lettuce harvesting machines were developed that use a water jet system to cut the vegetables. They have increased productivity threefold.

Digital Learning

Wheat combines were an obvious first application for robotics, but other crops have proven more of a challenge, and some fragile ones are still harvested by hand. These include delicate vegetables like asparagus, where labor accounts for 71% of production costs and 44% of selling costs. Certain ornamental plants and flowers also rely on human labor.

However, robotics are now being used for those, too. Machine learning is being integrated into new machines enabling them to mimic human behavior and visual perception so they can harvest delicate crops. For instance, Energid Technologies Corporation has developed a robotic citrus harvester that uses three-dimensional machine vision algorithms to make a computer model of an entire orange tree and store the location of each fruit. That information is then passed on to the machine’s robotic arms, which rapidly harvest the fruit.

Agrobot, a start-up in Spain, has developed a robotic strawberry harvester that has a camera-based vision system that analyses each strawberry individually based on color and form variations. The ripe ones are then cut from their stems and gently placed on a conveyor belt which leads to the packaging area.

Another area ripe for automation is crop dusting –the process of spraying crops with insecticides or fungicides from an aircraft. Crop dusters, the people who fly these planes, have the third-highest workplace death rate among US professions.

To tackle this dangerous task, 90% of crop spraying in Japan is already being done by small, unmanned helicopters. Robotic drones also have an environmental benefit: the precision application of pesticides to individual plants, or even to specific fruits growing on a tree, could reduce the use of chemicals by up to 80%. This dramatically decreases the amount of toxic runoff that ends up fouling rivers, streams and other bodies of water.

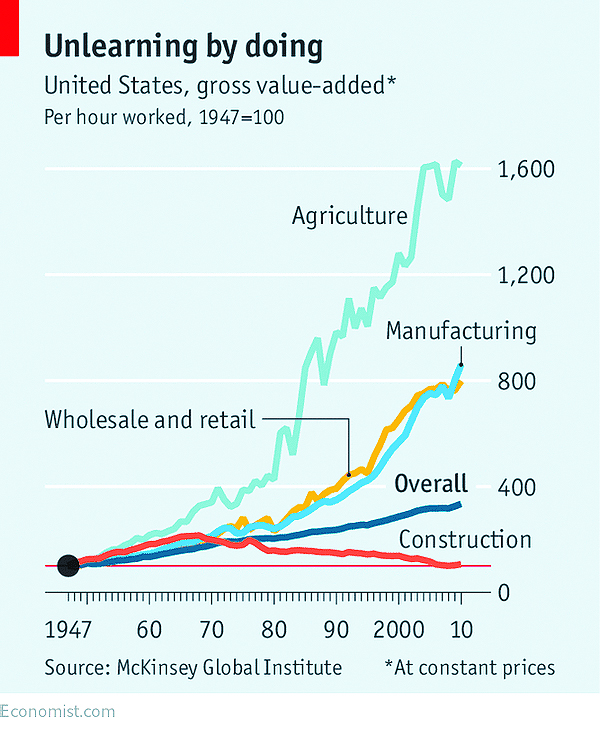

A massive investment in technology and automation has helped agriculture surpass other industries in terms of productivity. In the late nineteenth century, nearly 50% of US workers were employed on farms; by 2000 that fraction had fallen below 2%. Unemployed farmhands, who moved to cities in search of work in the manufacturing and service sectors, ended up earning higher wages than they had in the fields.

The Future of Building

So, how does this relate to the building industry? There are numerous parallels. Farmers and builders both face unpredictable site conditions and both are at the mercy of nature.

In addition, specific sub-sectors in each of these industries face unique challenges that are difficult to quantify. In construction, for example, the challenges faced by wood or metal framers are different from those faced by electricians or plumbers. That’s similar to agriculture, where each type of crop has to be maintained and harvested differently.

However, while agriculture has pulled itself out of low productivity and faced its challenges head-on, a lot of builders and housing manufacturers remain stuck in the past. There have been attempts to standardize construction with prefabrication, but for the most part, the process is still wasteful and relies too heavily on skilled labor.

That reliance has become construction’s Achilles heel. Older skilled workers are retiring and there aren’t enough younger workers to fill that gap. Builders are facing demands for higher wages, but can’t raise prices on their buildings enough to cover those increases and still be profitable. These issues have led to quality problems as well as a worldwide shortage of housing.

The fact that the construction industry didn’t get ahead of these problems is why it has one of the world’s lowest labor productivity rates. While other sectors have embraced automation and big data, these technologies have barely impacted construction. Attempts like robotic excavators and bricklaying machines haven’t been embraced on a wide enough scale.

But they will be. As this publication continually points out, labor and cost challenges are leaving the construction industry with no choice but to embrace 21st-century means of production. For those seeking a roadmap on how to mechanize and automate the jobsite and housing factory, agriculture provides a very useful example.