The winners will have the right people and a tech-focused offering that solves a tough problem.

- Thanks to high-profile industry failures and other factors, investors may scrutinize offsite companies more closely than other types of firms.

- The best way to attract a Venture Captial (VC) firm is with a technology that promises to solve a pressing industry problem, whether that’s selling homes, or manufacturing and delivering them more profitably to a wider area.

- An attractive company will offer market-specific, measurable benefits that can be used to counter objections from careful investors.

The news of late hasn’t been kind to privately funded offsite firms. It’s probably safe to say that everyone in the homebuilding industry has heard about Katerra and Entekra, two California-based offsite construction companies that shut their doors in 2021 and 2023, respectively. But those two high-profile companies weren’t the only ones dealt financial blows.

In the summer of 2023, Business Insider reported that Las Vegas, Nev.-based Boxabl, which captured national media attention with its flat packed ADUs, was being questioned by SEC regulators about its funding. More recently, SFGate reported that Hayward, Calif.-based Veev, an offsite manufacturer promising a unique panelized wall system embedded with technology, went belly up. That was in November 2023, just 18 months after the company, which had only completed a few projects, raised $400 million from investors. (Veev’s corpse has since been acquired and revived by Miami, Fla.-based Lennar. See Editor’s Note.)

Stories like these don’t make the task of attracting venture capital any easier. Combine them with information about the challenges faced by even successful offsite builders, then add a few dashes of interest rate volatility and labor and material shortages, and you’ve got a perfect stew to ward off shaky investors.

Going forward, how tough will it be for offsite construction companies to reap venture capital? Is there anything that offsite manufacturers can do to make themselves more attractive to investors?

Law of Attraction

Courting investors is similar to dating in that you’re more likely to attract the match you want if you can offer what that match is looking for. When it comes to investors, they will tend to check out the big picture before deciding whether to take a closer look. First impressions count.

Understanding how venture capital is structured and incentivized will help businesses best position themselves for that first cut. (See “A VC Primer” on this page.)

Overall, a long-term outlook helps here. “Every venture fund is, in essence, a 10-year partnership,” says Chris Langford, Managing Partner at Home Technology Ventures, in Davidson, North Carolina, and a Venture Partner at IDEA Fund Partners. “For the first three to four years of the partnership, a VC investor makes investments, and by years 10 to 12, we have to return that money back to our investors,” Langford says.

He points out that those investors generally expect a return of roughly three times their initial investment. “That, and the high mortality rate of early-stage companies, means that every company we underwrite needs to have home-run potential in order to make the math work,” Langford says.

Companies most likely to fit the profile for funding — the ones that make the first cut — should have two main characteristics:

1. A great team. A good funding candidate needs “an exceptional, world-class team with an understanding of how to build a company quickly,” Langford says. “They understand they are on the clock the second they take our money and must build a multi-billion-dollar business in a relatively short period of time.”

2. Great technology. He adds that the company profile needs to be technology heavy. “In theory, technology is a light asset — it doesn’t require buildings or raw materials — and it scales. Once you write software you can sell it to an infinite number of people with limited marginal costs other than the cost of sales and implementation.”

Despite the focus on raw materials and finished buildings, Langford doesn’t discount offsite firms from potentially receiving venture capital funding. But, he says, “there is a finite universe of people that look at companies where the main product coming at the back end is something physical in nature as opposed to technical in nature.”

Meeting Objections

An offsite manufacturer will face several challenges on the way to attracting venture capital. The most successful ones will be prepared to counter those challenges.

For one, asset-intensive businesses like homebuilding usually aren’t the first choice. Most venture capitalists are looking for “new-to-world, industry-defining type companies,” according to Langford. “They tend to invest in companies trying to do something exceptionally technically advanced, or different from what’s been done.”

While offsite construction isn’t exactly new, “only 3% of homes are built off-site today and the legacy industry is extremely inefficient, and rife with significant labor problems,” Langford says. “This paves the way for the most advanced companies with real intellectual property to raise venture dollars.”

Currey Cornelius, Managing Director Whelan Advisory, a New York-based investment bank focused on residential advisory services, takes a similar view. “Productivity of construction per hour worked has regressed since the 1970s while nearly every other industry has made massive strides,” Cornelius says. Technology that promises to improve that productivity could attract VC interest.

Like Langford, Cornelius also has a list of things that make VC companies reluctant to invest. These include: a limited delivery radius for many products, challenges in scaling up the business, the big upfront investment and ongoing overhead needed for a factory, industry insularity, housing cycles and the perceived risk created by those high-profile failures.

Another problem, says Langford, is company valuations. A firm is more apt to attract funding if it has the potential to sell for several times annual earnings, which isn’t the case in this industry. “Homebuilders don’t trade at really high multiples when they sell. Pure technology companies like WhatsApp may have zero revenue and sell for $19 billion, but that’s not an outcome that’s really achievable in the homebuilding market.”

The Particulars of Success

Companies that survive the first cut and counter the inevitable objections still must make a detailed case for why they’re a good investment. That case will revolve around the specific problems the company aims to solve.

Langford recommends focusing on the following areas of innovation.

- Technology. He likes companies that are focused on, “entirely digitizing the experience of buying a home from site selection to design and financing.” He calls this “going full stack.”

- Production. Creating a more efficient process can raise the potential for profit, and the odds of securing capital.

- Scalability. Another type of company that could be of interest to investors is one that can scale its operations. This could be done by increasing the radius it’s able to supply from a single factory, or by creating profitable micro factories.

Langford says that these three areas have attracted funding and have more legs than other areas. “Let’s imagine a brilliant team with an idea around a revolutionary technological or manufacturing system that’s going to solve a clear pain point within the housing value chain,” he says. “They can attract early money to build that initial prototype, get a first factory up and running, hire their first engineers and get going.”

Two examples of attractive companies are Plant Prefab and Mighty Buildings.

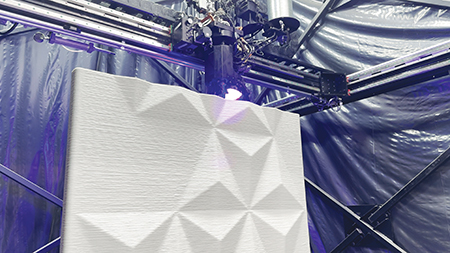

Plant Prefab is a Rialto, California-based company that’s creating what its website calls “an infinitely adaptable panel-based building system, driven by advanced engineering and produced with state-of-the-art manufacturing.” In December 2022, according to The Construction Broadsheet, the company received $42 million in series C and other funding. Mighty Buildings is an Oakland, California-based company that uses robotics and automation to create pre-built, factory-made 3D printed panels that can be customized to any plan.

Both companies have a value proposition rooted in technology, automation and scalability. “[We were] initially funded on the idea of material science,” says Alexey Dubov, Mighty Buildings’ Co-Founder and Chief Innovation Officer. “That’s our main differentiator in terms of doing prefab. On the other hand, we innovate throughout the value chain,” with 3-D printed panels and the use of automated robotics. “But material science is the true enabler of our benefits.”

When it comes to capital, Dubov says, “it’s less about how to get funded and more about how to bring new technology and innovation to market. The funding will follow if the company delivers.” And delivery — the factory-to-site kind of delivery — is particularly important to investors.

In fact, Mighty Buildings is working on increasing scalability and delivery. In late 2023, it received $52 million in funding from Wa’ed Ventures, Saudi Aramco’s venture capital arm, as well as from US-based BOLD Capital Partners. “[We’re looking at the] true potential of scale internationally, of homebuilding or manufacturing that can deliver solutions for different regions,” Dubov says. “In this case, the Middle East is quite attractive because they have a huge demand and because our technology is a great fit for the region.”

Cornelius points out that scalability and efficiency also feature in successful offsite companies such as Elkhart, Indiana-based Skyline; Maryville, Tennessee-based Clayton; and Volumetric Building Companies, with modular factories in California, Pennsylvania and Gdansk, Poland. “They do a wonderful job. The larger companies have factories across the nation. They have a model that works and are hyper-efficient.”

Demand is also an obvious feature that venture capitalists look for. “What’s happening upstream?” Dubov asks. “What’s going to create pull from the market rather than push from a supplier or manufacturer?”

He also stresses the importance of maintaining lean operations and strategic focus. “We’re not going to become a developer or a general contractor,” Dubov says. “That was a strategic decision to make sure we won’t fall into a trap in terms of optimizing our local maximums.”

Staying Focused

Cornelius, too, cites the importance of strategic focus and uses Katerra as an example of a company that tried to do too much all at once. He prefers companies that limit their scope. Truss and other component manufacturers are good examples of this because their products plug into the existing industry supply chain and have been widely adopted across the US.

He contrasts components to more complex systems. “Full modular products or kits of parts change the game quite a bit and require extensive strategic planning,” Cornelius says. Structural components meanwhile “are having an impact on construction efficiency and quality at scale, with more room for further adoption,” he says, citing Bain Capital’s 2020 investment and Platinum Equity’s 2023 investment in US LBM, which produces components and distributes specialty building materials. “It’s a real vote of confidence for the industry.”

Despite complexity, however, Cornelius is bullish for the offsite industry when it comes to private investment, including venture capital. “There will be more funding available because the problems are so clear and are getting worse, including the affordability crisis and the aging construction workforce.”

He also says that the media often focuses unfairly on failures, and doesn’t highlight the industry’s many success stories. “If an offsite construction model is streamlined, and focused not just on their product, but also on how that product is brought to the market, it can work and absolutely does work.”

Stacey Freed is a freelance writer and editor based in Pittsford, New York. She focuses on construction, remodeling, real estate, sustainability and wellness. Photos courtesy Mighty Buildings.