The use of modular on a big multifamily project means the developer must put up extra cash. But how much extra? And do the benefits outweigh that expense? A 2023 study offers some insight.

- Financing for modular projects is often less than that for site-built projects. In addition, interest rates are higher, and equity requirements can be as much as 30% higher, especially at the beginning of the project.

- Two real-world multifamily projects the author analyzed had LTC ratios of 75% for the site-built and 65% for the modular.

- Modular projects can be completed up to 50% faster than site-built projects, potentially yielding several months’ added revenue. The developer must decide if this outweighs the higher cash flow requirements.

Multifamily developers considering modular for the first time need to understand its advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, it can compress the construction schedule and speed up income generation. On the other, it requires the developer to put up more investment equity earlier in the project. There’s no free lunch.

Although most people in the industry understand these points, there has been scant data about real projects. I set out to address that in 2023 when, thanks to funding from a US DOE grant, I was able to compare the finance and cash flow requirements for site-built and modular construction. I hope that my findings will help developers make more informed decisions.

The Challenge

In a modular project, materials must be purchased and factory production lines reconfigured before work begins. Manufacturers require deposits of 30% or more of the contract cost, as early as three to six months prior to the start date, but often, lenders won’t finance these deposits.

Modular developers also usually face higher interest rates and lower loan amounts, and must deal with the fact that most modular manufacturers will not agree to retainage (the withholding of some of the contract fee until after work is complete).

To quantify these challenges, I started by interviewing a variety of manufacturers and lenders. Next, I created cash deployment schedules for two real-world, 200-unit multifamily projects completed in 2023. One was site-built and the other modular.

Background Research

I collected finance and cash flow data from factory visits and through interviews with seven manufacturers of volumetric modular units for multifamily construction. Together, these manufacturers have completed more than 50 projects since 2015, with an average of 150,000 gross sq. ft. of floor area each. I also collected data from three commercial lenders specializing in modular financing.

One piece of good news is that hard costs on a big project can be lower for modular, and can be locked in six months ahead of construction. The manufacturers I interviewed had costs ranging from $100-180 per sq. ft. for finished modules. Total costs for those parts of the building built with modules, including transport and placement, was 5-10% less than site-built. (This contrasts with single-family residential, where modular seldom costs less.) Projects were also completed more quickly.

Most lenders don’t consider modules as collateral until they’re in place on the project site, so loan-to-cost (LTC) ratios for modular projects are often 5-10% lower than for site-built, and interest rates are higher. In addition, some manufacturers invoice the developer every 15 days or less. These factors can further raise the developer’s equity burden.

For most projects, the modular portion of work represents 40-60% of the total project cost, and manufacturers often have owner-direct contracts with the developer. In these instances, there’s no GC markup on the offsite work, but the developer assumes more risk and must play a greater role in project coordination.

The real-world projects I studied fall in line with this background research. Let’s take a look at them.

Site-Built Costs

Our site-built example is a 200-unit multifamily building in Seattle, Washington. It consists of six stories of Type-III residential over one story of Type-I commercial (podium). Total construction cost was ~$45M over a project duration of 21 months.

Using a schedule of values and construction schedules provided by the General Contractor (GC), a cost-loaded schedule and project cash flow forecast were developed.

The cost-loaded schedule identifies each major construction activity; when it occurs, its duration, and its cost as a percentage of the total construction cost. From this information, we can determine the value of work completed for each 30-day ‘draw’ period, which is what the developer can expect to pay to the GC and its subcontractors and suppliers each month.

Construction costs averaged more than $2.0M per month, and exceeded $3.0M during some months. A 75% loan-to-cost (LTC) ratio provided about $33.8M in financing for the $45.0M project. As with most commercially financed construction projects, the lender will release its share of the monthly draw after work has been verified by an on-site inspection.

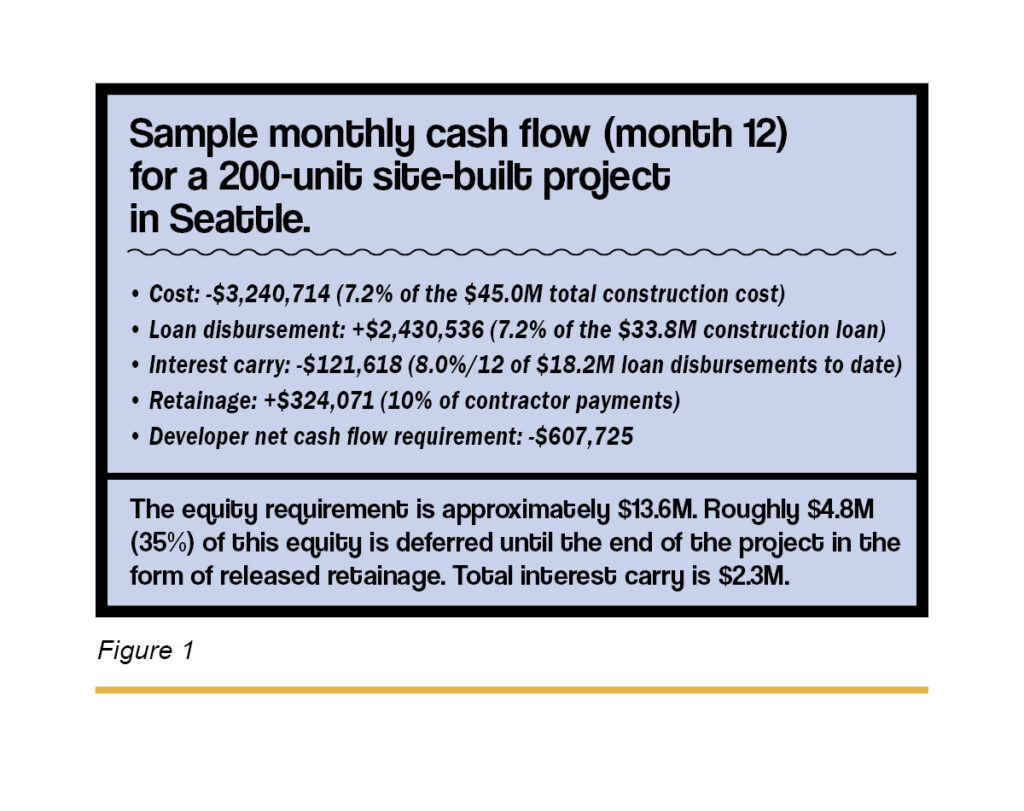

Imagine, for example, that the developer’s cash flow requirement for work completed in month 12 is $3.2M, or 7.2% of construction cost. The developer will request a disbursement of $2.4M, or 7.2% of the loan.

As loan funds are released, the developer incurs interest costs on the cumulative amount of funds drawn, which can either be paid in cash each month (e.g. ‘interest carry’) or from an interest reserve. For example, if the total value of work completed by the end of month 12 is $24.3M, or 54.1% of construction costs, the developer will have requested disbursement of 54.1% of the loan, or $18.2M. At an 8% APR, that would be an interest expense of roughly $121.6K for all funds borrowed up to that point.

Developers often withhold retainage on contractor payments until the project is substantially complete. Retainage is typically 5-10% of the contract, and provides the developer with a bit of a cash reserve.

Considering these factors, the developer’s net cash flow for a sample 30-day period (month 12) is in Figure 1.

Comparison to Modular

Our modular example is a 200-unit multifamily building in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Its specs are similar to the site-built Seattle project, with five stories of Type-III residential over one story of Type-I commercial (podium), and a cost at completion of about $45M.

Project duration was just 15 months, compared to 21 for the site-built example, a time savings of six months.

A cost-loaded schedule and project cash flow curve were also developed for this project. Overall, the offsite scope for 200 residential units on floors two to six was ~$27.0M, or about 60% of total construction costs.

The timing, duration and cost of the on-site part of the work was similar in the modular and site-built projects. Exceptions included MEP systems and interior finishes. In the modular example, the portion of this work done on-site was limited to common areas and corridors. (MEP and finishes for the dwelling units were installed in the factory.)

Jobsite overhead was lower, thanks to the shorter construction schedule. The manufacturer’s direct relationship with the developer reduced the on-site scope and the GC markups on subcontractors, which also lowered costs for the developer.

The total cost for the modular project was roughly 5% less than the site-built. However, the modular project required a line reservation fee and material deposit of $8.1M, or 30% of the modular contract paid at least in part by the developer three to six months in advance of production, a major cash flow burden.

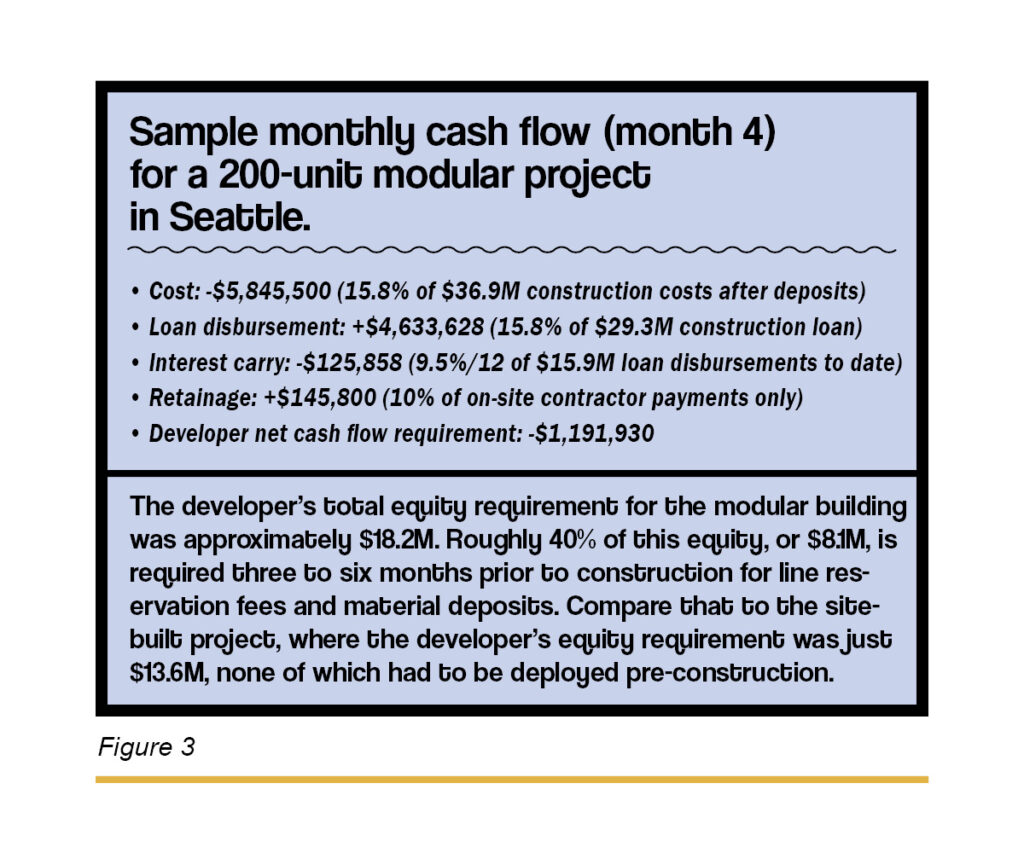

According to industry standards, the modular manufacturer would have assessed an ‘online’ fee of 30-35% for each module start and, an ‘offline’ fee of 30-35% for each module finish, invoiced monthly. For 40 modules started and completed in month four, for example, the manufacturer would have invoiced the developer $4.4M.

For this project, a 65% loan-to-cost ratio would provide approximately $29.3M in financing. This may be a lower LTC ratio than for a site-built project if the lender considers the loan ‘unsecured’ until the modules are delivered and set in place. Often, the unsecured portion of the loan is underwritten against the developer’s credit, resulting in an interest rate of about 9.5% (versus 8% for the conventional project).

And again, the developer generally can’t withhold retainage on payments to the modular manufacturer, as it does with other suppliers and contractors. Considering these factors, the developer’s net cash flow for month four is summarized in Figure 3.

Conclusion

As these two examples show, the developer’s equity burden can be as much as 30% more for a big modular multifamily building than for a site-built one. More of that equity must be deployed at the beginning of the project because the pre-construction modular fees and deposits are often not covered by the construction loan.

A modular project may also have to settle for a lower loan-to-cost ratio and a higher interest rate. The inability to hold back retainage on the modular manufacturer’s work creates an additional cash flow burden.

Despite these challenges, however, modular offers real benefits — as long as the developer can handle the extra cash flow burden.

For instance, the fact that the modular project in this study was finished six months earlier than the site-built project meant that rent-paying tenants could be put in place that much earlier. In addition, modular construction is safer, more efficient and less susceptible to weather delays, labor shortages and other problematic site conditions.

There are signs that the financing challenges may improve. For instance, the Associated General Contractors of America (AGC) has published a new suite of contracts for modular that addresses some of these issues. In addition, some lenders are starting to specialize in modular, which should mean more favorable financing terms and conditions.

I may write about these developments in a future article. For now, however, any developer considering a move from conventional building to modular will have to decide if the cash flow challenges justify the benefits, and will have to come up with more cash earlier in the project. I hope this article helps with that decision-making process.

Kevin Grosskopf is a Professor at the Durham School of Architecture, Engineering & Construction at the University of Nebraska. He has a PhD in Architecture, an MS in Construction Engineering, and several years of experience as a construction manager. The full 2023 cash flow study is available at OffsiteBuilder.com.