No, they don’t make things like they used to. Here are seven reasons why.

- Planned obsolescence isn’t a new phenomenon, but it seems to apply to more new products than ever, including most new homes

- The ways that products are designed to wear out or need replacement aren’t always obvious

- There’s a market edge in building with durable rather than non-durable products and systems, but only if buyers understand the difference

My two-year-old GE fridge recently stopped working. It made a clicking noise every couple of minutes, which I assumed was the compressor trying to start up, but it never did. I found some helpful YouTube videos diagnosing the problem and I replaced the start relay and capacitor, but couldn’t get the fridge up and running again.

A new compressor costs over $500 and hiring a technician to replace it costs a couple hundred more. As much as I was trying to avoid it, I bought a new Samsung fridge from Costco to replace my GE fridge. It comes with a 10-year warranty on the compressor, which I hope I won’t have to replace.

This frustrating and disappointing experience is the result of “planned obsolescence.” It’s a business strategy in which items are designed to be obsolete, unfashionable, unusable, or defective after a short period. This forces us to throw away things that aren’t very old and to purchase replacements at a higher price point.

Planned obsolescence results in higher profit margins for manufacturers and supports an economy driven by rabid consumerism.

While most discussions of planned obsolescence are about things like electronics and fashion, this curse also shows up in the homes we live in and the building construction industry as a whole. In this article, I discuss different types of planned obsolescence that are causing our homes and buildings to fail.

The first is contrived durability. Manufacturers purposely reduce the lifetime of a product so that it deteriorates quickly, usually right after the warranty ends. They use inferior materials in essential parts, which include cheap plastic screws instead of metal that are too susceptible to wear and tear. My GE fridge is an example of contrived durability—it had a one-year warranty and died in just two years.

This isn’t new. In the early 1900s, the Phoebus cartel—an oligopoly that controlled the manufacture and sale of incandescent light bulbs—intentionally reduced the life expectancy of light bulbs from 2,500 hours to 1,000 hours. They even fined manufacturers for bulbs that lasted more than 1,000 hours.

Nowadays, we’re being encouraged to switch from incandescent to LED bulbs, which claim to last 30 years. From personal experience, this is a lie. I’ve bought LEDs from Amazon that didn’t last for more than four months.

On a larger scale, homes are designed to meet the minimum Building Code requirements. Builders use nails to secure walls to roof rafters instead of more durable metal straps. They also use nails to anchor walls to a foundation rather than more expensive bolts. Cardboard thermo-ply sheathing has replaced OSB or plywood in some markets. While all these decisions are allowed by code, they can collectively reduce the lifetime of a building.

Next is the prevention of repairs. Unibody designs or soldered parts prevent owners from repairing products. Replacement parts are also expensive and difficult to find. This has turned traditionally durable goods into single-use, disposable items.

- Apple uses tamper-resistant Pentalobe screws on their laptops and iPhones, which is seen as an attempt to lock owners out of their devices.

- Panasonic’s infrared toaster oven can bake food 40 times faster than normal. However, the on/off switch is soldered to the circuit board. When it stops working you have three choices: buy an expensive new circuit board, spend hours removing this tiny plastic part, or throw it away.

- Front-loading washing machines have a drum bearing that is prone to wear and tear. Repair costs are higher than the value of the appliance, so customers just purchase a new one.

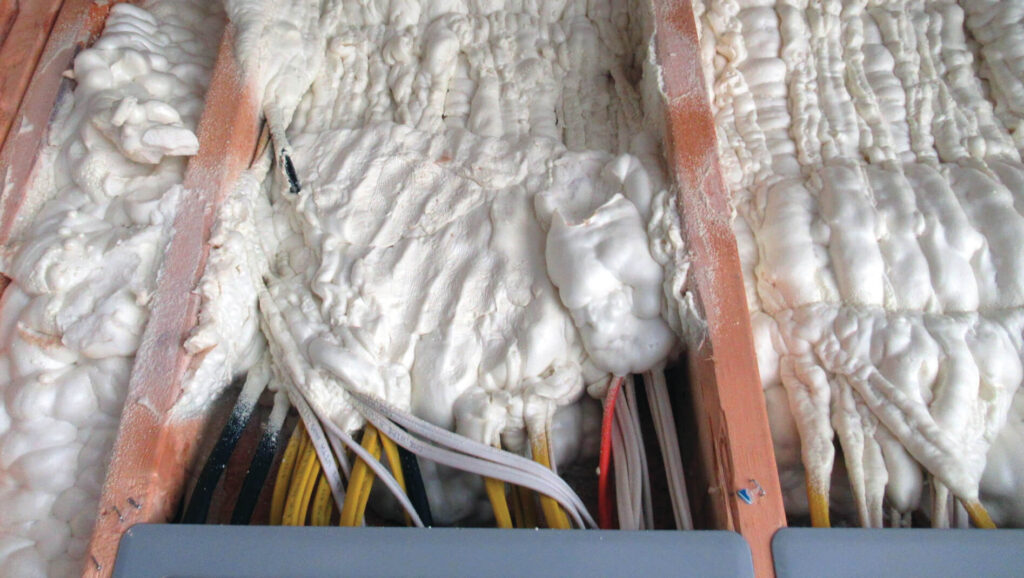

And then there’s spray foam insulation. When applied correctly, it can create an air-tight building that helps reduce HVAC costs. However, electrical wiring and plumbing is embedded in the insulation, which will make home repairs and remodels a nightmare. We should be separating the insulation from the infrastructure.

Systemic strategy deliberately ensures that the current version of a product will become outdated and incompatible with newer versions.

This is evident when charging ports are changed on laptops and TVs. You have to spend money on dongles and adaptors just to be able to use your old products.

In January 2020, the EPA banned the production of R-22 refrigerant, or freon, which was widely used in air conditioners. This is a good thing for the environment since freon can destroy our ozone layer. But the ban has made repairs ridiculously expensive so homeowners have to throw away old condensers and buy inferior new ones.

Another example of systemic strategy is changing floor designs. The laminate flooring in my current home is just five years old but has already started chipping. Since I can’t find this particular pattern anywhere, if I want to repair it I have to replace the flooring in my entire home.

Programming or design decisions can also lower the life expectancy of materials.

In many cities, it is illegal to shut off the water supply at the curb without permission from the utility company. But not every house has a valve inside. The freeze in Texas last winter flooded many homes and apartments because they weren’t able to shut off their water supply.

Some tiles are laid directly onto concrete floors that move, without a cleavage membrane-like compressed sand or a Schluter mat that can absorb small movements. This leads to cracked and sometimes popped tiles.

Foundation repair is a huge business in the Dallas Fort Worth, Texas area where I live. Most homes have either had foundation repairs in the past or will need them in the future. This is because soils here have a high clay content; they swell and shrink throughout the year. Despite knowing this, most new homes have slab-on-grade instead of pier and beam foundations. What’s worse is that contractors are now moving to post-tensioned slabs, which will be far more expensive to fix in the future.

Legal intervention is another planned obsolescence strategy.

I made a video for my YouTube channel a while back on all-electric homes. In the 1960s, coal-burning furnaces were banned and new homes that only used electricity were awarded with a “Gold Medallion.” Ironically, these Medallion homes were powered by coal-burning power plants, so they were not “clean” in any way.

During a recent visit to Canada, I was told that wood-burning fireplaces are now banned. However, those new electric fireplaces won’t work in a winter blackout, which means that residents won’t be able to keep their homes warm or even cook meals.

Perceived obsolescence is our fault.

We are guilty of buying into marketing campaigns and changing trends. We are guilty of becoming shopping addicts and indulging in retail therapy. I’d be lying if I said that my new Samsung fridge isn’t sexy, but I guess that’s a sign I’m getting old.

We recently bought a 1970’s home that has a 40-year-old HotPoint stove top and GE microwave that still work. Sure, they’re not trendy, but they’re functional. There is nothing I can buy to replace them that will work for the next 40 years.

Countertops trend from ceramic tiles to laminate, to granite, to solid surfaces, to engineered stone like quartz. Fridge styles change yearly too, from top freezer to bottom freezer to side-by-side, to French door. We’re told that color trends change yearly and that wallpaper is coming back in style. Maybe I should just leave this loud blue wallpaper in place.

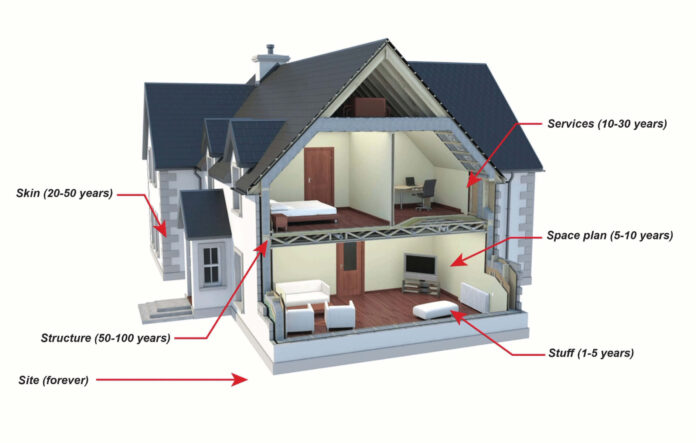

Finally, there are layers of change.

This is a very important part of planned obsolescence in the construction industry. Barring a natural disaster or planned excavation, the land the home is built upon should remain basically as is forever. The typical home will last 50-100 years. Siding is good for 20-50 years. Services (pipes and wires) last 10-30 years. The space plan will be “current” for five to 10 years. Furniture and other stuff will last one to -five years.

Homes are designed such that the longer-lasting components are dependent on the shorter-lived ones. For example, obsolete insulation can only be replaced by removing long-lived façade or roof elements. Even though a concrete slab should last 100 years, it will have to be broken up if you need to repair the pipes beneath it. In other words, we are intentionally lowering the lifespan of long-lasting materials.

Both manufacturers and consumers are to blame for this current state of affairs. The dopamine and serotonin released from buying new gadgets is very addictive, but that feeling is being weaponized by manufacturers through planned obsolescence. Consumers are told that overflowing landfills and polluted oceans are our fault when, in fact, it’s corporations that are the problem. They waste energy and resources designing disposable products that fail and then turn around and call themselves “green.”

We need to demystify homes and educate homeowners. I believe that every home should come with an instruction manual detailing where things are located and how to identify them. Public education on planned obsolescence and the right to repair will help people focus on the bones and performance of homes. This shift will finally force developers and contractors to build better.