Real innovation will require a move toward Industrialized Construction. But, for that to happen, industry companies need to embrace new business models.

- Vertically integrated Industrialized Construction (IC) companies have great control over all processes, but require lots of capital and a very clear market focus.

- Orchestrators assemble a team of business partners to create and hone products that can be built again and again. Capital requirements are relatively low, but they are highly dependent on their partners.

- An Offsite Spinoff is an IC company that’s started or acquired by a more conventional firm. The parent can share expertise with the spinoff and is also protected from risk. However, it can be a challenge to find qualified talent.

Why does the building industry have such a hard time innovating? One reason is the way companies are structured. Modular and other offsite approaches have the potential to make builders more efficient and productive, but these gains won’t be realized if everyone clings to old ways of doing business.

A more productive future is one in which conventional offsite firms are replaced by those that embrace what’s called Industrialized Construction, or IC. If you’re interested in investing in one of these companies, however, you need to understand the ways in which they’re structured and how that structure helps them innovate.

To find out more, we spoke with Daniel Hall, Assistant Professor in Management of the Built Environment at the University of Technology at Delft, Netherlands. His research has identified the three most common business models for Industrialized Construction (IC) companies: the Vertical Integrator, the Orchestrator and the Offsite Spinoff.

This article examines each of these models. What are the benefits of each? What are the pitfalls? First, however, we need to define what we mean by IC.

What is Industrialized Construction?

Hall co-wrote a chapter called “New Business Models for Industrialized Construction” in Industry 4.0 for the Built Environment, published in 2022. He and the other authors explain that it’s a mistake to think of IC as simply a matter of rejecting on-site craftsmanship in favor of offsite manufacturing.

The truth, he says, is that most established offsite companies are fairly traditional: they bid on individual jobs and some build in a conventional manner, albeit under a roof.

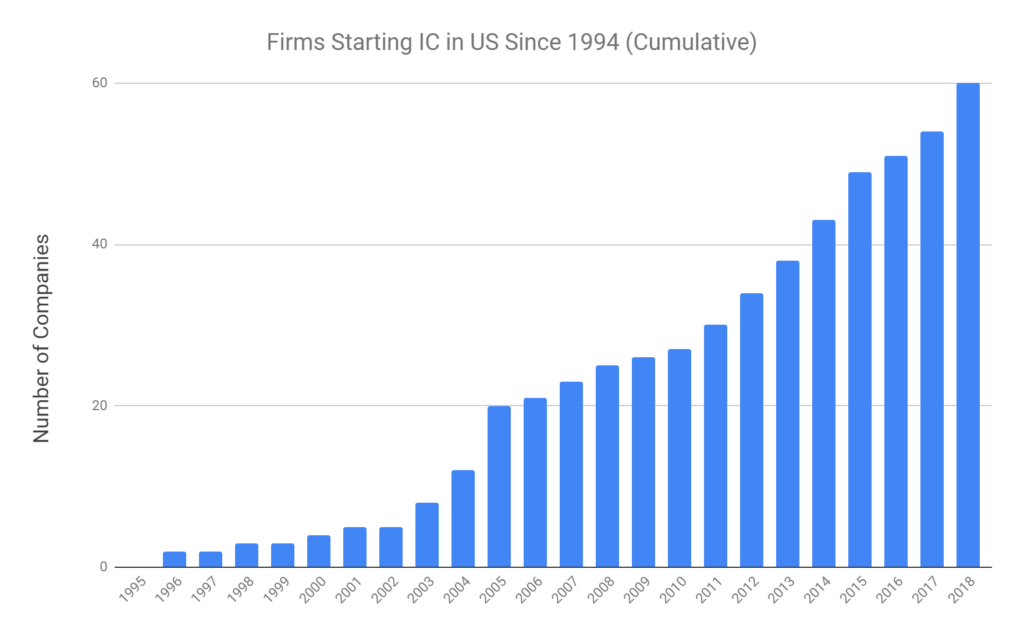

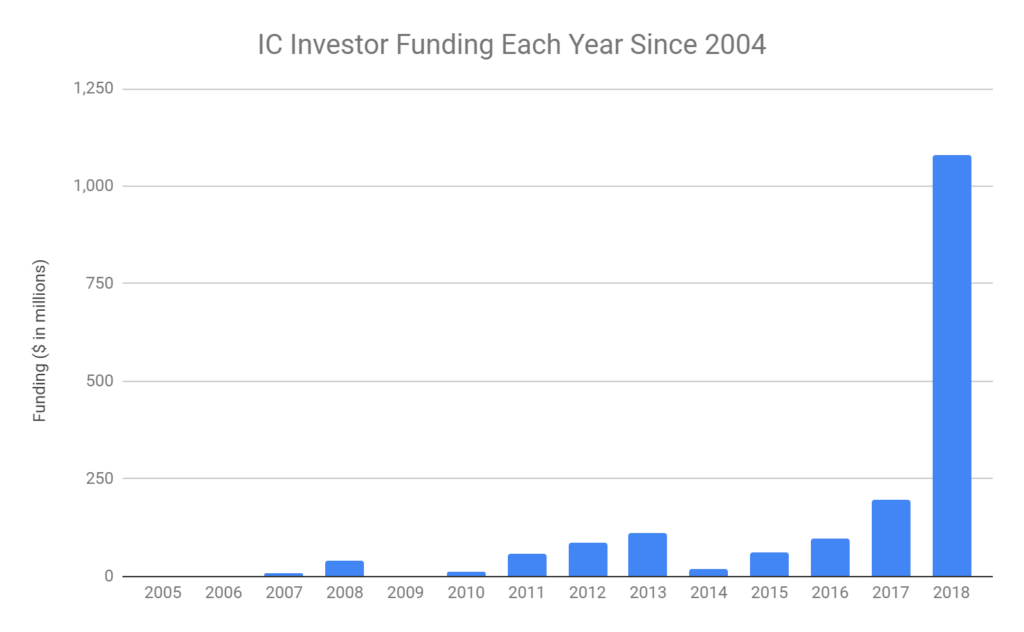

Of course, building indoors has advantages even if nothing else changes and Hall acknowledges that many of these companies “know what they’re doing and are very successful.” But they’re not necessarily ‘industrialized’ and don’t attract the amount of venture capital funding that IC companies do.

Real industrialized construction companies embrace alternative business models, meaning they’re not structured around competitive bidding for the lowest cost on individual projects.

In conventional construction, team members (contractors, subs, suppliers, etc.) are often selected based on cost. They come together temporarily for a single project and then disperse. They’re unable to innovate because knowledge and relationships aren’t easily, or fully, transferred and/or developed from project to project.

Take the example of robotics, which has the potential to make the industry more efficient and better able to provide housing at lower cost. To truly optimize designs, products and process for robotics, you need a stable team of designers and manufacturers who work together across various projects over time.

This type of consistency has characterized other industries for decades and is part of the reason they can produce better and better products — such as cars that are safer than ever, use less gas and can easily go for 200,000 miles or more. This consistency is also a hallmark of an IC company.

Now, let’s dive into those three business models, including the pros and cons of each.

Vertical Integration

Hall says that vertically integrated IC companies reap benefits across time, over multiple projects. Vertical integration allows greater control over the entire process of creating a building, and it allows expertise and knowledge to grow and transfer from project to project.

One example of a successful vertically integrated company is BoKlok in Sweden, founded in 2006. The company builds wood-framed homes using what its website describes as “a smart, industrialized and efficient process.”

According to Hall, BoKlok’s vertical integration gives them a high degree of control. “They’re able to control design, to make sure they’re designing to a target cost, and to ensure they have continuity in all their manufacturing and construction processes.

BoKlok isn’t the only one doing business this way: there are also successful, vertically integrated companies in North America. They include Blox (Bessemer, Ala.), Intelligent City (Vancouver, B.C.), and Volumetric Building Companies (Philadelphia, Pa.).

The main disadvantage of vertical integration is that it’s very expensive. You need a huge amount of capital to fund the equipment and expertise needed for a modular factory, as well as for site work, module setting and finishing. “The factory alone is a hungry beast,” says Hall. “It has to be fed constantly, because every moment it’s not producing something, money is being lost on capital investments.”

What happens if that capital isn’t put to good use?

The most infamous example is Katerra. In Hall’s view, Katerra didn’t fail because it was vertically integrated, or because it acquired other companies. Rather, Katerra got into financial trouble and failed because it was unfocused.

The company agreed to a wide variety of work, thinking they could build anything for anyone — just like a traditional project-oriented GC. That was a fatal decision, Hall says, because being the manufacturer as well as the builder requires you to narrow your offerings. “Focus is essential. You need to decide which products you will make. You need manufacturing lines that stay busy making those products. And you need to say no to making anything else.”

If you’re considering vertical integration, it’s also crucial that you be an expert on the product you’re manufacturing and that you have a deep understanding of the market for that product. Once you achieve some success with that focus, you can think about expanding.

For instance, in 2022 Volumetric Building Companies merged with Polcom, a Polish manufacturer of steel modular buildings for the hospitality industry. But it only made that move after a successful 13-year track record focused on modular multifamily buildings.

The Orchestrator

(For an in-depth profile of an Orchestrator company, read An Expandable Panelized Home, in this issue, too.)

As mentioned above, in traditional construction, a general contractor brings together disparate parties — based largely on lowest-cost bids — to act as a team on a single project. In contrast, an orchestrator firm (also known as a digital systems integrator) brings together disparate parties to act as a team to create a product line that can be used across multiple projects.

Orchestrators tend not to own a lot of infrastructure, such as factories. Instead, they collaborate with suppliers — of wall panels, MEP systems, steel frames, floor cassettes, etc. — and “orchestrate bringing these ingredients together to provide a product they offer to the market,” Hall explains.

Over time, the products and processes involved may be revised and improved. For example, the orchestrator’s ongoing manufacturer relationships mean it can work with manufacturers to improve how a steel rafter attaches to a steel column and to tweak the design accordingly. The result is continuous improvement across projects, such as faster assembly times or buildings that can be constructed in earthquake zones. “This is how Toyota works with their suppliers,” Hall says. “They co-create solutions to improve the resulting products.”

Orchestrators avoid competitive bidding between their suppliers, says Hall. They won’t switch suppliers just because they found one that’s 10% cheaper. “Their savings over time come from the continuity of working together across projects.”

The orchestrator business model works well with a product platform approach. This is where various well-defined parts can be put together in different ways. Lego is the most-cited illustration: it includes parts that can fit together in various ways to build things that are very different from each other.

However, the way pieces fit together is rule-bound. You can’t assemble them any old way. For a specific construction project, the orchestrator brings together a complete kit of all the parts needed for that project. (Just like a Lego kit for building a model of Hogwarts Castle.)

The advantage of the orchestrator approach is its low capital outlay. A successful example is Project Frog, founded in 2006 and based in San Francisco, Calif. It supplies prefabricated buildings to educational, retail and healthcare clients.

The company does not own or operate the factory. Instead, they have partnerships with various manufacturers and suppliers, as well as with the local contractors who assemble the buildings. Frog designs the buildings, manages the supply chain and oversees the build process.

The main disadvantage of this business model is its potential lack of control. If there’s just one supplier for a particular assembly, and if that supplier is busy, the orchestrator firm may not be able to take on a project. The solution is to have enough partners to guarantee a back-up plan. This may not be possible in some markets: there may not be enough logistically feasible suppliers with the right level of expertise.

Another pitfall Hall mentions is “interface management,” which means that it can be tricky to get parts from various suppliers to fit together perfectly. “In conventional construction, experienced field workers are talented at making things fit together on-site,” he says. Parts don’t have to line up perfectly for crews to make them work.

With multiple companies involved in the orchestrator approach, product development — from design through manufacturing to transportation and assembly — can take longer than with a vertically integrated operation.

For this approach to work, the orchestrator’s suppliers must be willing to help perfect how all the parts connect. For efficiency, the parts must fit together easily and quickly on-site. And that process of perfecting the product can be slow when it involves multiple companies.

The GC Spinoff

The third business model, according to Hall, is one in which an existing, project-based business starts an IC division. This is done by creating spinoff factories.

One company that took this approach is DPR Construction, a commercial general contractor and construction management firm headquartered in Redwood City, Calif. Founded in 1990, they currently rank as one of the top 50 general contractors in the US, with 28 offices around the country.

In 2017, DPR created a spinoff in Phoenix, Ariz. called Digital Building Components, which designs and builds prefabricated components — walls, decks and partitions — for commercial, institutional, hospitality and multifamily buildings.

The spinoff approach allows close connection and knowledge sharing between the two companies. But because the spinoff is a separate business entity, there’s minimal impact on the parent if it fails. Digital Building Components’ independence also makes it free to develop expertise that DPR lacks.

The parent company “may not know how to deliver a digital model that can be fabricated, may not know how to create designs that are efficient for manufacturing, may not know how to hire the right talent, and so on,” Hall says.

DPR had the advantage of prior experience with trade contractors who brought prefabricated wall panels, utility racks, large pieces of ductwork, and so on, to their on-site projects. That experience reduced the risk when founding the spinoff company.

However, Hall cautions that it can be a challenge to find the people you need for this approach. “It’s very difficult to find a senior manager with both construction management experience and industrial engineering experience.” Hall says. Both are needed.

Another way for a GC to expand into industrialized construction is to acquire, or take a partial share in, an existing offsite manufacturer.

In 2017, Canadian company Bird Construction took a stake in Stack Modular, which has offices in Canada, California and China. Stack was already successful at manufacturing modules in China and shipping them across the Pacific to North America. Bird could take advantage of that expertise without having to create it from scratch. In return, Stack Modular gained the advantage of built-in demand for modules for use in Bird’s projects.

As you grow your offsite business, or if you’re looking to get involved in the offsite industry as an investor or as a company founder, we hope this article is a helpful introduction to the three most common business models in industrialized construction.