Debunking the “housing variety as a barrier to mass production” hypothesis.

- The author challenges the notion that consumer demand for some customization is a constraint on more efficient building methods.

- Production homes are already mass-produced on site, and most housing developments only offer a small number of different floorplans.

- Further variety tends to be a function of colors, finishes and other minor tweaks—things that a well-managed factory can accommodate.

An idea I frequently encounter is that a barrier to the mass production of housing is the amount of variety people demand. People want unique homes and aren’t interested in living in a neighborhood where their house is identical to their neighbors’ homes. The idea is that the demand for variety is difficult to accommodate with any sort of mass production.

I think there’s little evidence to support this idea. Empirically, many (likely most) new housing developments in the US consist of a small number of floor plans copied over and over again.

For instance, there’s a development by DR Horton (the largest homebuilder in the US), with about 50-60 homes. There are just seven different floor plans, repeated over and over.

I bought a newly-built home last year in a development with the exact same pattern: 50-60 houses, with a small number of floor plans. (My house is in a row of about eight houses that all have the same floor plan.) The same developer is building another development about five minutes away that’s very similar. My in-laws, who bought a recently-built house a few years ago in a different state, also live in a similar development of several hundred houses with a small number of repeated floor plans.

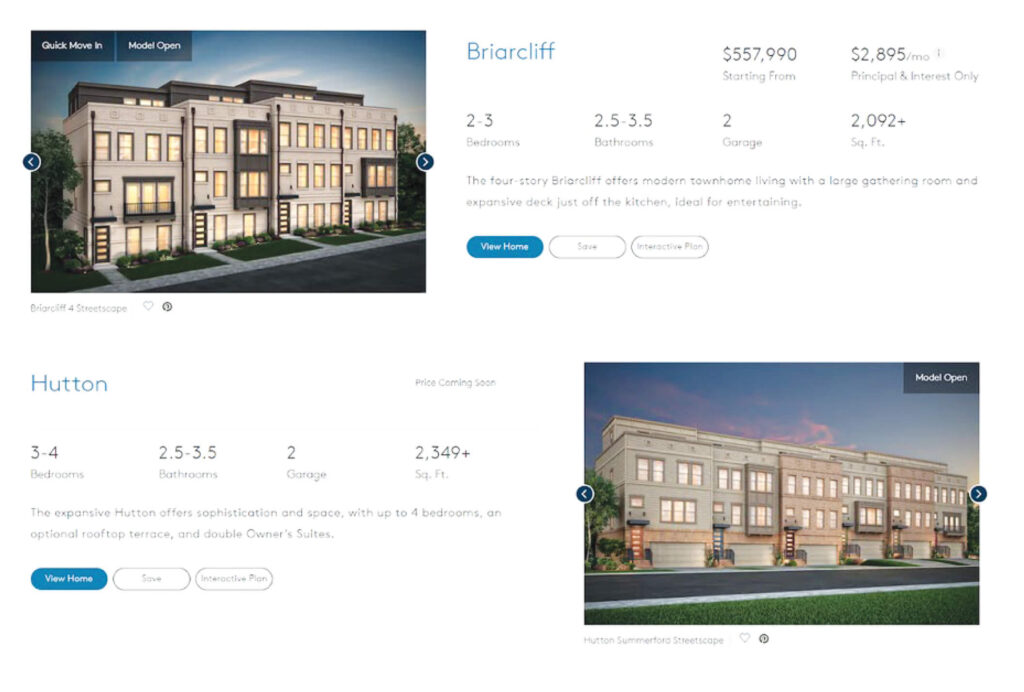

These are all single-family homes. If you look at townhouses, you see even more repetition. For instance, these two developments in Atlanta, Georgia by Pulte share the same two floor plans repeated over and over again (though they offer quite a few configuration options for them, letting you change some of the room layouts or adding an extra floor for the Briarcliff model).

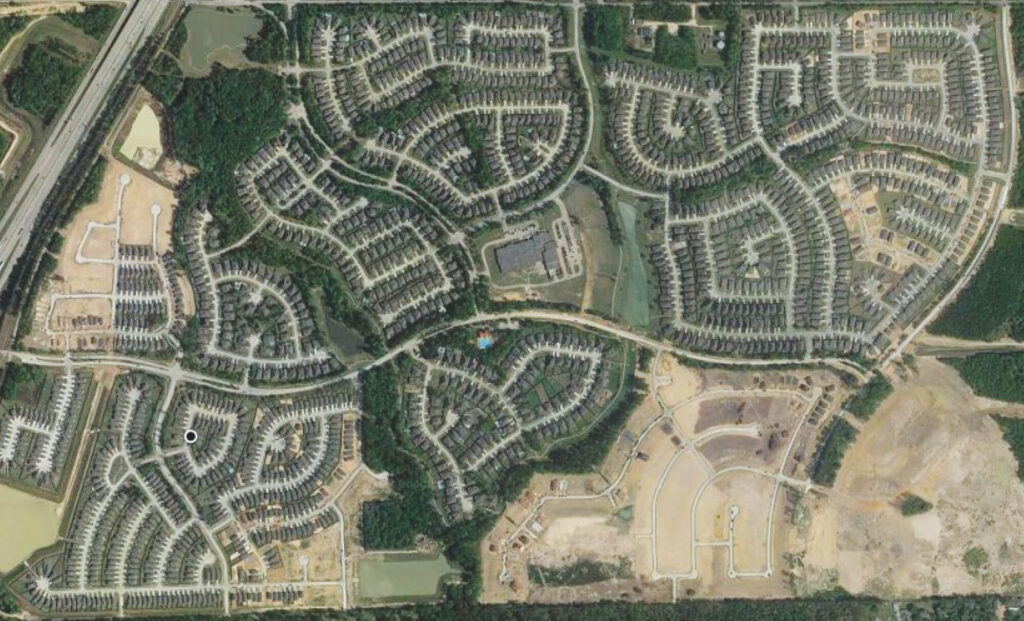

And if you look to the north of the second Pulte development on a map, you see two other townhome developments by other builders, which also appear to consist of two to three designs, repeated over and over.

If you look instead at apartment buildings, you see the same thing – buildings or developments typically have a small number of units that just get repeated over and over again in different configurations.

For example, The Oliver is an apartment building in Atlanta with 285 units and 12 different floor plans. The Cortland Uptown Altamonte in Altamonte Springs, Florida has 300 units that have nine different floor plans. There are countless other examples.

In fact, some multifamily developers go farther than this. They have standard buildings (where each building consists of a standard unit arrangement) and they build it over and over in different developments.

So it doesn’t seem like the “housing variety as a barrier to mass production” hypothesis is true. That it seems true —in that we do see a lot of variety in housing options —is a function of a few different things.

For one, it’s relatively easy to squeeze a lot of aesthetic variety out of few basic designs. By changing exterior colors and finishes, mirroring the floor plans, and making relatively minor tweaks (such as adding an entryway overhang, or changing a hip roof to a gable roof) your seven different floor plans can quickly become a much larger number of configurations that don’t look identical at first glance.

This is nothing new. If you look at floor plans for Lakewood, a huge suburb built in California in the 1950s, you see that each one typically had several aesthetic variations — different exterior trim, different types of roofs, etc.

Homebuilders will also often offer different finish options (different flooring, fixtures, countertops, appliances, etc.) that can easily be changed without fundamentally changing the design of the house. This sort of variation isn’t incompatible with mass production methods — car models, for instance, also have different trim levels, paint colors, interior materials and other configuration options that can be extensive.

Another factor is that the US homebuilding sector is extremely fragmented:

The top four homebuilders (DR Horton, Lennar, Pulte, and NVR) accounted for 20% of the single-family home market in 2021, compared to over 54% of the US market for the top four car manufacturers, and 75% of the market for the top four industrial robot manufacturers. As of 2017, there were an estimated 66,000 homebuilding firms in the US.

If we look at real estate developers, we see even more fragmentation. The largest US multifamily developers, for instance, build fewer than 10,000 units a year, or just over 2% of the 370,000+ multifamily units built in a year in the US.

These developers will all use their own floor plans and home designs. So, a lot of housing variation is just a reflection of the fact that the US has a lot of homebuilders.

Housing also lasts a long time and it tends to accumulate variation as it ages. Sometimes this is because parts or components wear out and are replaced by different ones. When my parents needed to reroof their house, they replaced their tile roof with cheaper asphalt shingles.

Sometimes it’s because the occupants adapt the house to better suit their preferences. The homes on my street, for instance, are less than two years old, but people are already adding outdoor terraces, three season porches, or fences so they can let their dog out. Even a group of houses that start out identical won’t be identical for long.

Similarly, housing trends change over time – different materials and styles come in and out of fashion and changing demographics, wealth, family structure, or technology end up reflected in different housing styles. US homes got larger over time as the country got wealthier, the arrangement of the kitchen changed as it went from a utility room to family gathering and coordination room, people started to prefer more bathrooms. Materials become cheaper, or more expensive — four-sided brick homes gave way to homes with brick on just the front facade, or just as an accent. So homes built in one time period will look distinct from homes built in previous time periods.

And housing variety is often imposed/demanded by other sources than the buyer. Sometimes different sites will demand different housing designs because of their layout, orientation, or other relevant features. If a site slopes on one side, for instance, that might require some houses to be split level, or to have walkout basements. Floor plans might need to be massaged to squeeze enough rentable square footage onto a site to get the required return on investment. Zoning approval might be contingent on changing the amount of glazing or masonry used.

So overall, I don’t think buyers demanding large amounts of variation is a binding constraint on developing more efficient methods of building.