Debunking five big misconceptions

by Belinda Carr

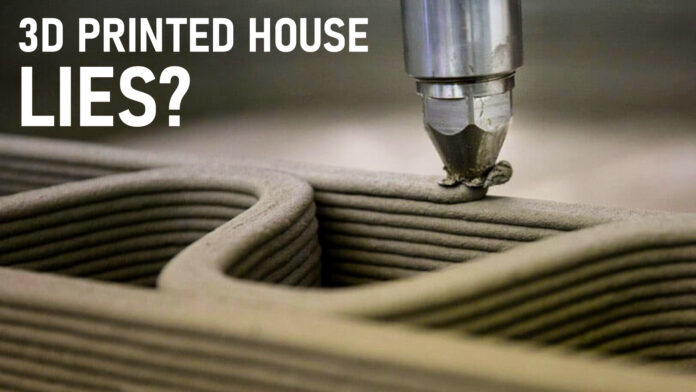

3D-printed concrete homes are a hot topic on social media, with millions of adoring fans worldwide. Unfortunately, the space is littered with fake news, hyperbole and a lack of critique.

In this column — and the linked video at the end of this article — I examine the claims made for these homes, and consider their advantages and drawbacks.

Claim #1: 3D-printed homes can be built for less than $4000

This is a flat out lie.

Some journalists misled people for the sake of clicks by claiming that Austin-based ICON 3D’s $10,000 tiny home prototype would only cost $3500 or $4000 when printed in large quantities. To their credit, ICON 3D categorically denied this claim.

This is a new field with many unknown variables, including cost. Every company uses a different printer and concrete mix and none of them have printed homes in large quantities.

ICON 3D, Logan Architecture and 3Strands have teamed up to build four 1,016 square foot houses with 2 bedrooms and one-and-one-half baths for $450,000 in Austin, Texas. While this is comparable to homes in the area, only the first floors were printed; the upper floors are stick framed.

It is important to remember that cost-effectiveness varies by market. Before the blip in lumber prices, stick framing was the cheapest option in the U.S. CMU (concrete) block construction is the cheapest option in Middle Eastern countries like the U.A.E. Steel or masonry bricks are the cheapest in other areas.

Although 3D printing reduces labor costs compared to stick framing, it comes with other expenses: the cost to rent or buy the printer, the electricity needed to run it (which is exorbitant in some countries) and the cost of hiring specialists to calibrate and operate it.

Claim #2: A home can be printed in 24 hours

No, it can’t.

3D printers create walls, not homes. That 24-hour claim ignores the time needed to install windows, doors, roofs, electrical wiring, plumbing, insulation, HVAC systems, interior walls and finishes, millwork, etc. It also ignores the time to ship the machine, offload it, set it up, calibrate it, and dismantle it.

A viral video from 2014 claimed that a Chinese company, Winsun, printed 10 houses in 24 hours. However, they were running four printers and only printed wall sections. Everything else was assembled by humans. Those homes also had no plumbing.

A family in France was the first to move into a 3D-printed home in 2017. The walls took 54 hours to print but windows, doors, roofing, appliances and cabinetry took another four months. The outside of the home was manually finished with smooth plaster.

The walls of this home are actually 2 layers of polyiso foam with poured concrete in the voids. Polyiso needs to be sprayed in a temperature -and humidity – controlled environment, so the entire site was tented.

A better alternative could be stacking ICF (insulated concrete form) blocks with plastic webs then filling them with concrete the conventional way.

Claim #3: 3D printing will eliminate construction jobs

We are a long way off from that.

3D-printing companies are often driven by outsiders from the tech field. They believe that they can fix construction’s productivity problems by automating the entire industry without having any knowledge of its intricacies.

They think that 3D printing is to construction as Tesla is to cars. It’s not.

A Tesla can be driven anywhere in the world with relatively small tweaks. By contrast the construction industry has to contend with endless variables: soil conditions, weather, local materials, culture, economy, design codes, and of course, form and function.

The global construction industry also relies on thousands of specialized trades. Improving coordination between these trades is an ongoing struggle that the printing of walls doesn’t solve.

Claim #4: 3D-printed homes can solve homelessness

The arrogance of designers and architects really shines when they talk about homeless shelters.

Making a shipping container or 3D-printed concrete shelter will not solve homelessness. We need to approach the issue with humility and address the underlying socio-economic and psychological issues among other things.

A case in point is LaFargeHolcim’s ambitious plans to build affordable, low-carbon housing and schools in Africa using 3D-printing technology. Is this realistic?

I spoke to Nicholas Patel, the founder of Fullbore Africa, who grew up and ran several construction businesses in Kenya. His perspective was eye-opening.

He pointed out a lot of challenges, including: the lack of consistent power, the need for several backup generators, the carbon emissions involved in shipping the machine to Africa, the poor infrastructure for getting to job sites, the legal issues clearing the expensive 3D printers at ports, 24-hour security, cost of foreign-trained specialists to run the machine and their hazard pay, the fact that dirt and sand will get caught in the grooves of a 3D-printed structure, and the difficulty in getting high-quality, consistent windows and doors to fit into the precise openings created by 3D printers.

Light-gauge steel framing would be a better option for this region.

Claim #5: 3D printing is sustainable.

Generic claims of sustainability over other forms of construction are untrue.

The building industry accounts for 40% of all energy-related carbon dioxide emissions, of which cement accounts for 8%. It is responsible for almost one-tenth of the world’s industrial water use. It adds to the heat-island effect. Limestone quarries and cement factories are air pollutants. Accelerants added to concrete to increase curing time can pollute indoor air.

That makes concrete one of the most environmentally destructive materials on earth. Also, walls are a tiny portion of the entire structure. We need a holistic approach to construction to make it truly sustainable.

My Conclusion

Don’t get me wrong, I am excited about 3D-printed construction, whether it’s concrete, mud or synthetic stone. I love the raw, layered appearance of 3D-printed homes. I even made a video on this technology a couple of years ago.

I don’t think the technology is a gimmick, but I despise the sensationalist coverage, misleading claims and over-promises. They generate a lot of buzz and probably help fund startups, but I think the lies cheapen the technology’s value.

Although 3D printing has potential, it’s still in its infancy and comes across as a solution looking for a problem. However, I’m confident it will find its niche.

I see many parallels between the hype and media coverage of shipping container homes and 3D-printed homes. I hope this column and the linked video will help industry professionals understand the limitations of this technology, so they can make intelligent choices on where to use it.

Belinda Carr is a Dallas-based building science researcher and content creator. The video version of this article includes more detail and is available on her YouTube Channel: YouTube.com/BelindaCarr