Government-financed housing projects are a large potential market for modular. This Minneapolis team shows us how to win the work.

- The city of Minneapolis, Minn. was looking for “missing middle” housing, meaning multifamily buildings of four to 10 units each.

- The modular team offered the right blend of experience. In addition, the accelerated project timeline meant the city could start earning revenue sooner and would qualify for tax credits.

- Despite being “affordable,” public housing tends to be relatively expensive to build. Project teams need to be prepared for this.

Photo courtesy of: DJR Architecture

By reviewing a recent case study, this article aims to share important information with modular manufacturers who want to get involved in public housing projects by responding to RFPs (Requests for Proposals) issued by municipalities and public housing authorities.

After receiving responses to an RFP they issued, Minneapolis Public Housing Authority (MPHA) decided to use modular construction to build several rental homes in the city. What was the selection process like? What made them choose modular? And why did they settle on the specific team they did? What was it about the designs for the project that appealed to them?

The Project

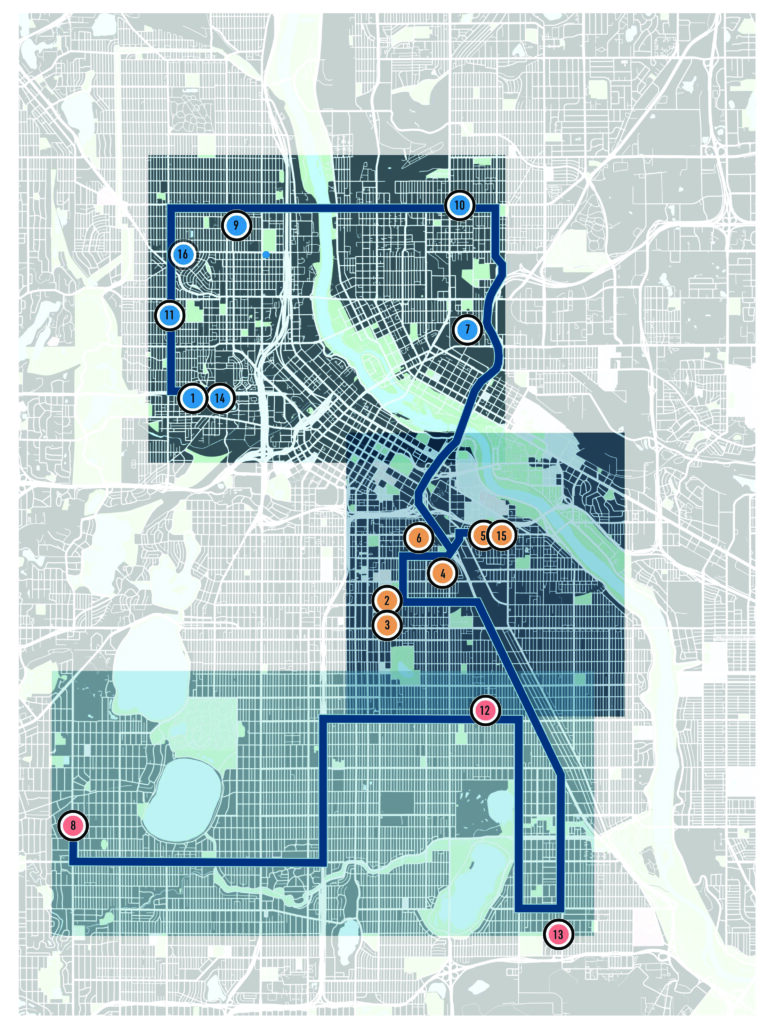

The MPHA-owned rental homes were to be built on 16 city-owned sites in 12 neighborhoods across Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Amanda Pederson at DJR Architecture was the project manager. She was involved with the project “from the RFP response all the way through to the punch list.” The project team consisted of DJR and Rise Modular, both in Minneapolis, and Frerichs Construction of St. Paul, Minnesota.

Pederson describes the rents for these units as “deeply affordable, [which] in this context, refers to housing for people whose income is at or below 30% of the median income in the county.” MPHA has a sliding scale for rent, with the amount paid dependent on the tenant’s income. “It’s hard for private developers to reach goals like that,” she says.

In addition to affordability, the homes aimed to fill a gap in the type of housing available in Minneapolis. Pederson explains, that “missing middle” is a term used in architectural and planning circles that describes apartment buildings that are relatively small, with four to 10 units. She says that while these smaller buildings are rare, “they’re critical infrastructure because they provide increased density that fits into the context of a single-family neighborhood a little bit better.”

She believes that that “missing middle needs to happen across all income brackets.”

The 16 sites that MPHA had available were scattered across the city in neighborhoods that consisted mostly of single-family homes. Effective from January 2020, Minneapolis eliminated single-family zoning, which means that multifamily buildings can be built on lots that had previously been designated for individual homes — so long as they meet other requirements, such as lot size and easy access to public transit.

On those 16 sites, the team built a total of ten, 3-story six-plexes (9 modules each) and six, 2-story four-plexes (6 modules each). This amounts to 84 apartments and a total of 130,000 sq. ft. of housing. They include 3-bedroom units with just over 1300 sq. ft. of floor space and 2-bedroom units with about 1100 sq. ft.

Photo courtesy of DJR Architecture

The Request for Proposal (RFP)

The RFP didn’t specify modular, so Pederson’s team was competing against conventional construction. “But the RFP did mention that [MPHA] was interested in modular because they saw its advantages for this scattered-site project — having overlapping processes and being able to reduce the construction timeline,” Pederson says.

There were eight responses to the initial RFP, three of which included modular. MPHA chose three teams (the DJR team, as well as a conventional builder and a third team that was willing to do modular or conventional construction) and gave each a $7500 stipend to produce drawings and conceptual designs that could be priced out. MPHA used these to make their final decision.

The ultimate choice of DJR was the first time MPHA had decided to go with modular construction, and some staff members were nervous about the risk of having a single entity (the manufacturer) responsible for half of the construction costs. However, because of the advantages they expected to realize, they decided to take the risk.

For example, to qualify for tax credits (via the federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit program) the project had to be completed in no more than 18 months. So, speed was important, and modular construction has a distinct advantage in that respect. DJR also knew that finding enough available contractors and subcontractors to work on multiple smaller scale buildings in the time span needed would be difficult. It would have been easier if it had been one big building on a single site. Prefabrication was an alternative way of centralizing most of the construction work.

Although they ended up not entirely avoiding it, they also hoped to avoid winter construction work. In addition, they wanted residents to move in as soon as possible, and neighbors to be inconvenienced for as short a period as possible. And, crucially, Pederson says, “Saving time is saving money. Every extra month of construction is extra interest paid on construction loans.”

MPHA chose Pederson’s team, specifically, because all members had significant relevant experience. In addition, DJR had already worked with Rise Modular on six or seven modular projects, and MPHA had previously worked with Frerichs Construction. The price and schedule were also compelling. In addition, it was a benefit that all members of the team were local to the Minneapolis-St. Paul area.

How Long Did It Take?

Initially, Pederson’s team proposed a timeline of 11 months, but once they gathered more information and had a greater understanding of the project, this was revised to 13 months.

The deal closed in November 2022, and they broke ground in December 2022. But due to permitting and financing delays, manufacturing in the Rise Modular plant didn’t start until April 2023, later than initially planned. Because of the delays, the original production window was missed. “You can’t have the factory sitting idle, so a project did slot in in front of ours,” Pederson says.

But “once construction started, the timeline went as planned,” she explains. The first building was completed 10 months after breaking ground, in October 2023, with the others being completed one by one over the next three months. The final building was completed in January 2024, 13 months after breaking ground.

MPHA has a waitlist of 7500 households, and this project has just 84 units. Nevertheless, it was a step in the right direction. “Getting 84 units built quickly was important to our agency’s mission of helping to get families housed,” a spokesperson for the agency says.

Design Work

Pederson explains that designing affordable housing isn’t very different from designing market-rate homes. “Everyone’s housing needs are essentially the same,” she says. That said, some design changes were made after consulting with potential residents.

“Residents had a lot of impact. Originally, when we first designed the kitchen, it was U-shaped with the sink looking out the window. For cost reasons, MPHA considered a galley-style kitchen,” Pederson says. “That was one of the very first things that residents noticed and said they needed more storage in the kitchen [than was available in the galley-style kitchen]. Generally, larger families are living in these units, and they cook a lot at home. So, we increased the size and the amount of storage in the kitchen.”

The other main difference was having a dedicated dining space, “not just a bar counter like you often see in market rate,” Pederson says. Residents also wanted darker kitchen countertops that wouldn’t show stains as much as a light color. “They weren’t as concerned about things like the size of bedrooms. And they were also very much in favor of exterior fencing and motion-sensor exterior lighting.”

“We had four color palettes and, although some people loved the bright colors, some of the residents associated brighter colors with affordable housing and they wanted the building to look market rate, so they wanted more neutral colors,” she says.

How Much?

Despite this being affordable housing, project costs were significantly higher than for building market-rate apartments. Pederson says, “Public housing has strict procurement guidelines regarding how they go out to bid, how many bids they need to get, how a project’s bonded and how much labor is paid; the Davis-Bacon Act requires workers to be paid locally prevailing wages.” The complexity of a scattered site (versus all the units being on the same site) also added to the costs.

The owners (the city) also wanted very high-quality, durable finishes so they wouldn’t have to keep updating. (Market rate is often sold after a few years, with new owners updating to suit.) In addition, residents want high-quality and continuous insulation and other energy-saving features to keep energy costs down. “Solar panels were essential — both for reducing long-term operating costs and allowing access to additional funds from the bank,” Pederson says.

On average, each unit cost about $600,000. But the savings from reducing the construction timeline by using modular rather than conventional construction were significant: over $100,000 per month. So, shaving five months off the schedule is half a million dollars saved on the overall project costs.

All costs were borne by the city, and the rents were still below market rate.

Zena Ryder writes about construction and robotics for businesses, magazines, and websites. Find her at zenafreelancewriter.com.