An in-depth look at how an alternative factory model can solve prefab’s economic problem.

• Microfactories relocate fabrication to the jobsite, boosting utilization, reducing CapEx and avoiding centralized factory inefficiencies.

• Portable automated units deliver fast, precise, customizable components, with examples ranging from AUAR to Cuby and Reframe.

• Emerging models include leased fleets, subscription access, localized supply chains and regulatory shifts enabling flexible on-site manufacturing.

Prefabricated construction has always meant large, fixed factories churning out modules or panels that get shipped to building sites. But that centralized model — made infamous by companies like Katerra, General Modular Homes and Skender — has faced challenges, including large up-front CapEx (Capital Expenditure) Requirements and hefty shipping costs.

The emerging microfactory model flips that script. Take a compact, automated production unit (often the size of a shipping container) and set it up next to the jobsite. The factory becomes a portable product, and the building compon-Ents are made where they’ll be used.

By making factories shippable and components locally produced, microfactories capture the benefits of off-site fabrication (automation, efficiency, indoor conditions) without the drawbacks of centralized production.

What Is a Shippable Microfactory?

A shippable microfactory is a compact, self-contained production unit that can be deployed on or near a building site. It combines automation, modular equipment and digital coordination to enable localized, on-demand manufacturing. It can perform tasks like cutting, framing and assembling parts using software-driven automation.

Each project’s digital design feeds directly into the microfactory’s machines, so that components can be custom fabricated on demand. Whereas a conventional facility is large, stationary and optimized for high throughput (but with high overhead), a microfactory is small, movable and deployed per project.

Portability is the real breakthrough here. Once a project is finished, the factory can be packed up and shipped to the next job. The factory itself becomes a productized tool that a builder can deploy as needed, rather than a permanent asset that need always be kept busy.

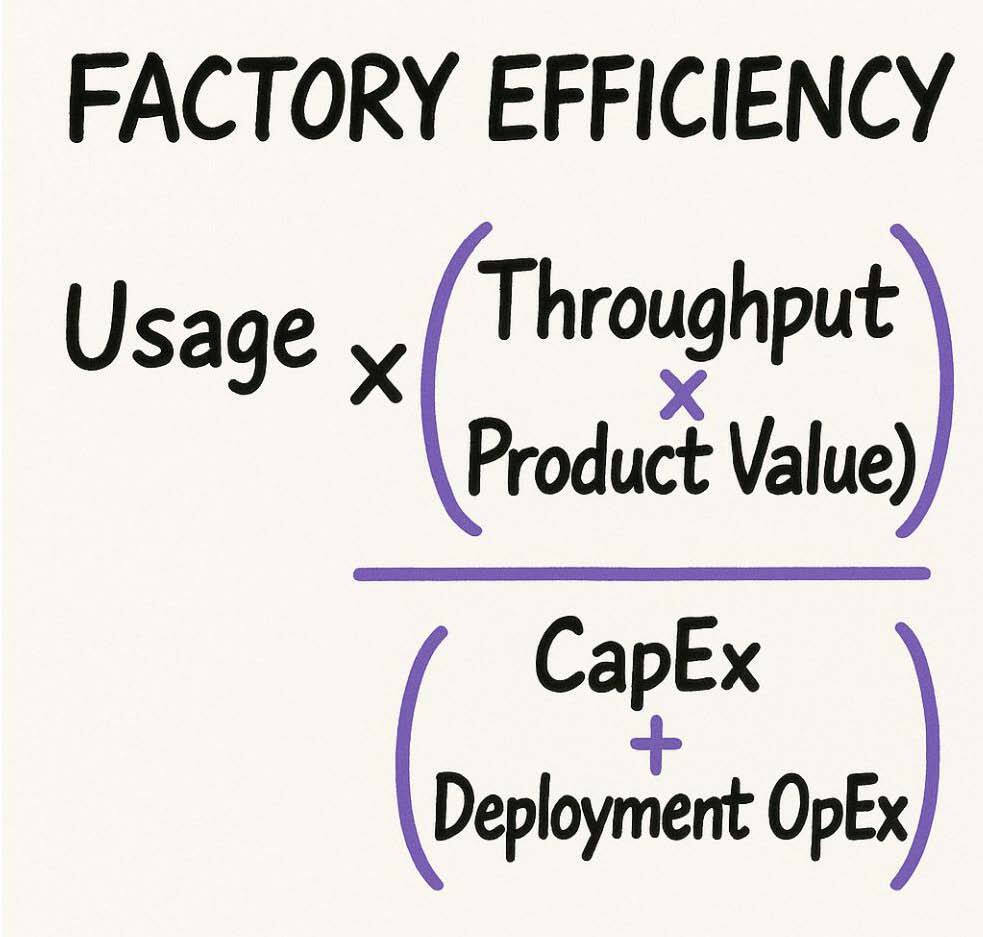

The Factory Efficiency Equation

How can we determine if any factory is economically viable? One useful lens is factory efficiency, which measures the value of output produced relative to the cost, adjusted for the level of utilization.

A simplified expression is as follows:

Factory Efficiency (or FE) = Usage × (Throughput×Product Value) / (CapEx+Deployment OpEx)

• Usage is the fraction of time the factory is actively producing. Throughput is the production rate (e.g. units per month).

• Product Value is the value (or revenue) per unit produced.

• CapEx is the capital cost of the factory equipment.

• Deployment OpEx (Operating Expenditure) is the operating cost to set up and run the factory for the project (labor, maintenance, site power, etc., excluding raw materials).

A higher FE value means more output per dollar of cost, when normalized for utilization.

This equation highlights the tradeoff between scale and utilization. A traditional large factory might have very high potential scale/ throughput, but if it’s only running at 50% capacity because of bumpy demand, its effective efficiency plummets. The denominator (high CapEx and overhead) remains high, while the numerator (throughput × product value) is under-realized, driving up the cost per unit.

Low effective efficiency has plagued many modular construction firms. When demand is irregular, factories often run below optimal capacity. Some end up chasing far-flung or low-margin projects just to keep their assembly lines busy.

By contrast a microfactory can be packed up afterwards and reused, increasing overall annual usage. Its capital cost gets amortized over multiple projects and its CapEx is often an order of magnitude lower than a mega-factory. This makes breakeven throughput more achievable on a small pipeline of work.

The Equation in Action

British Offsite recently built a new high-volume prefab facility in the UK for £45 million, targeting a 4000 homes per year capacity (about £11k of factory investment per annual unit). Even if a shippable microfactory costs around £0.5 to £1M, that’s on the order of just £3k to £6k of CapEx per home per year, significantly less capital per unit of output.

Multiple microfactory units can run in parallel to boost throughput when needed, but a builder can start with just one or two, dramatically lowering the entry barrier. The deployment OpEx for a microfactory (site setup, a small crew, utilities) is also relatively low and tied only to project duration.

The Equation in Action

From a unit-cost perspective, microfactories aim to meet or beat conventional construction costs while adding efficiency. Consider a few benchmarks for context.

On-site stick framing. Building a house frame by hand costs $7 to $16 per sq. ft. In the US, just for carpentry labor.

Structural Insulated Panels. A SIP costs between $10 and $18 per sq. ft. For the panel itself (materials only, not installed). That’s a higher per-ft. Cost than raw lumber, because you’re paying for factory labor and fabrication.

Framed wall panels. Prefabricated wall panels cost more upfront per sq. ft. Than raw lumber. However, overall project cost can drop after factoring in the on-site labor savings, reduced waste and faster schedules.

When robotic advancements continue to bring speed of production higher and the overall cost premium lower, what do you expect to happen to the adoption of microfactories?

Configurations and Use Cases

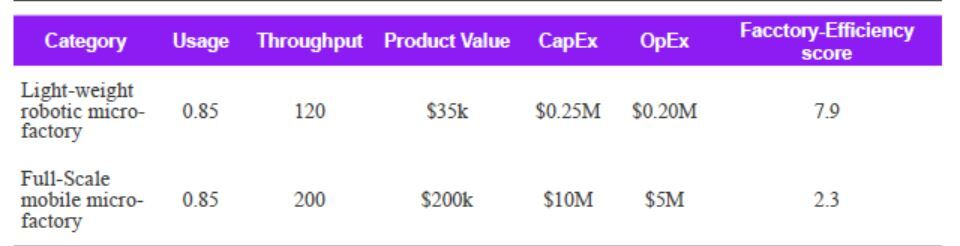

Shippable microfactories for home construction vary by level of onsite deployment, capital intensity and scope of work. At one end are lightweight robotic setups that handle only structural framing; at the other are large-scale mobile plants that output nearly complete homes. There are also hybrid approaches that use alternative fabrication processes like 3D printing or CNC cutting.

Below is a mapping of this range, with examples.

Pop-up Automated Framing Stations

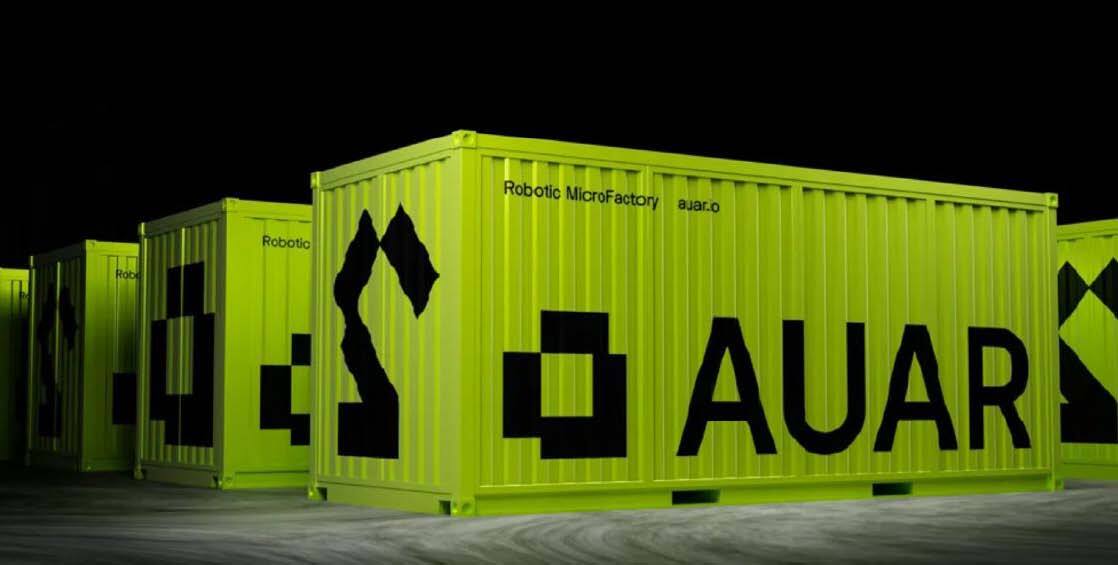

At the low-capital end, companies like AUAR deploy compact robotic factories focusing on structural shell fabrication. For example, AUAR’s unit comes in a standard container and assembles timber wall, floor and roof panels using an integrated robot arm.

This containerized system can be shipped to a site and made operational within weeks. Because scope is limited to the structural envelope, the machinery is relatively simple (a few robotic work cells), and the upfront investment is minimal.

The system can erect a full singlefamily home shell in about 12 hours with an unskilled crew. Conventional trades still need to handle mechanical/electrical fitout and finishes, but the overall project timeline and labor requirements drop substantially. This category of microfactory is ideal for a developer or homebuilder looking to scale framing efficiency and/or production.

AUAR even offers a leasing option so that a builder or developer can simply lease the microfactory as projects arise. The monthly fee is based on usage.

Full-Scale Microfactories for Turnkey Building

At the upper end of the spectrum are integrated microfactories that act as full general-contracting plants under one roof. Cuby is the clearest example: its deployable facility includes dedicated stations for structural framing, bundled MEP assemblies, insulation and interior prep, producing a complete kit-of-parts ready for rapid onsite assembly.

A single Cuby factory costs roughly $10 to $15 million to commission (a good upfront investment, but light compared to a regional prefab plant) and can turn out hundreds of homes per year. Cuby selects sites with deep, steady demand within a 200-mile radius. The plant need only capture about two hundred units annually to run near full utilization. The builder or developer gets factory-level productivity without the logistics burden of long-haul module shipping.

Reframe Systems (Reframe) follows the same turnkey logic but at a smaller footprint. Its local “robotic microfactory” cranks out closed panels and volumetric modules with pre-installed insulation, windows and services, chasing Net-Zero performance targets. CapEx is reported in the low single-digit millions, and output is sized for a metro-area pipeline rather than a single master-planned community.

Like Cuby, Reframe sells the promise of factory precision and schedule certainty, but anchors the plant close enough to projects to keep trucks, labor and capital cycling at high speed.

These heavy-duty microfactories are best suited to builders with multi-year volume commitments. They deliver factory efficiency and consistent quality while keeping designs configurable for local codes. The trade-off is operational complexity and a higher capital stake up front, so the model only pencils when reliable throughput can justify the spend.

Alternative On- Site Methods

A hybrid approach is exemplified by the UK’s Facit Homes (Facit), which brings a microfactory to the site in the form of a containerized CNC machine. Facit’s system digitally fabricates custom timber components (think of large interlocking plywood pieces forming a structural chassis) right on-site, tailored to each unique design.

The CNC router sits in a shipping container that is moved from one home to the next, cutting panels and structural elements that are immediately assembled a few meters away. This method saves on transport logistics and enables fully bespoke architecture without the overhead of a permanent factory.

Checking the above examples against our equation, the math confirms that keeping CapEx granular and movable, while running near full utilization, unlocks an order-of-magnitude advantage in factory economics for construction. Even assuming the same usage, low CapEx changes the game.

Now let’s look in more detail at a single example.

Case Study: AUAR’s On-Site Robotic Factory

What does a shippable microfactory look like in practice? One of the first real-world deployments comes from UK-based AUAR. (Disclaimer: Shadow Ventures, the company in which I’m a General Partner, is an investor and has permission to share this data.)

In late 2024, AUAR completed a two-story office building in Belgium using a robotic on-site microfactory. This pilot project was fully manufactured using a single compact robotic work cell set up at the construction site.

AUAR’s shippable microfactory (essentially a robotic arm with specialized tooling, housed in a container) fabricated all the structural components of the building: timber wall panels, floor cassettes, roof elements, etc. According AUAR, this was one of the first buildings in the world produced entirely by a robotic system in a temporary, deployable factory.

Less than eight hours of machine runtime was needed to produce all the components for the structure. For context, stick-framing that structure by hand might take a crew several days or more; here, it required just one business day of automated work.

The microfactory provided the precise “core and shell” components. Human tradespeople did the interior finishes, MEP (mechanical, electrical, plumbing) systems, insulation and exterior cladding, much like a normal build. This hybrid approach (automate the heavy structural work, then assemble the rest) strikes a balance between factory precision and on-site customization. According to the local building partner, the robotic cell reduced framing labor time by roughly 80% and compressed that portion of the schedule from one work week to one shift.

AUAR also intentionally varied the design (different window sizes, placements, etc.) to prove that a single microfactory can handle non-repetitive builds without losing efficiency.

Scaling Challenges

Shippable microfactories are still in their early days, but their role in construction is poised to grow. Here’s what I’d expect to see in the coming years.

Technical hurdles. There are many technical issues that need to be solved before microfactories can offer a true breakthrough. For instance, the robotic system needs to calibrate itself in a dusty yard, sense warped lumber, drive nails to tolerance and flag errors so a single low-skill operator can simply press go.

Power demands. Most construction sites lack the required 480 V three-phase power. There needs to be an integrated step-up transformer or battery skid that guarantees stable current without a utility upgrade.

Material variability. The system has to auto-tune cutting and fastening for spruce today, LVL tomorrow, or even light-gauge steel, with no tooling changeover.

Design flexibility. Finally, the design stack must run structural calcs, code checks and toolpaths in minutes. This ensures that a house plan drawn at dawn can flow into production the same day.

Microfactory Fleets

Instead of one factory per company, builders might operate multiple microfactory units as a coordinated fleet. For a large development, they could dispatch five to 10 microfactories to work in parallel, or spread units across a region for many smaller projects.

Managing such a fleet will require advanced scheduling and logistics software (possibly AI-driven) to allocate factory units efficiently. We may also see specialized service firms maintaining fleets of microfactories and renting them out (akin to equipment rental). This would let construction companies scale their prefab capacity up or down as needed by adding or removing microfactory units.

This model turns construction into a decentralized network of mini factories that pop up where needed. Early signs of this are already emerging; some startups offer “factory-as-a-service,” where developers lease mobile production units along with training and support.

Low CapEx/ Subscription- Based Deployment

The business model is likely to shift toward a subscription or payper- use approach. As mentioned, AUAR and others are providing microfactories on a no-CapEx lease, which lowers adoption barriers. In the future, a contractor might subscribe to a microfactory like a cloud service — e.g. paying a monthly fee or dollar amount per sq. ft. Of panel produced, which includes the equipment, software and support.

The subscription model aligns incentives: the provider keeps upgrading the tech (since they retain ownership and want longterm users), and builders get predictable costs and flexibility.

As manufacturing becomes a rentable utility, even small construction firms could access cutting-edge automation on a project-by-project basis. This shift from upfront investment to operational expenditure could change how projects are financed and executed.

Localized Supply Chains

As production becomes more distributed, building material supply chains will need to adapt. Rather than one big factory receiving massive shipments of lumber or steel, a network of microfactories will need materials delivered to temporary sites. This could give rise to more localized supply hubs.

Also, fewer large modules would need to be hauled cross-country, reducing long-distance freight. Overall logistics could become leaner and more local.

Local communities might prefer this model since it keeps more economic activity (and jobs) in their area rather than in a distant factory. One can envision a large project where material vendors, microfactory units and assembly crews all co-locate on a “mobile construction campus” for efficiency.

Regulatory and Code Adjustments

The rise of on-site fabrication cells will pose new questions for regulators and inspectors. Traditionally, offsite-fabricated components (like modular units or roof trusses) are subject to separate factory certification.

A microfactory building components at the jobsite blurs the line. Is that considered offsite manufacturing (needing a thirdparty factory approval) or on-site construction under the normal local inspection process? Clear guidelines will be needed.

Shippable microfactories grew out of prefab’s hard lessons. Instead of funding a distant plant that ships components, we can now ship the plant itself. A containersized, digitally guided line can be dropped where the work is, run at near full utilization and then be moved when the pipeline shifts

That keeps the numerator — throughput and value — high while holding CapEx and OpEx in check. Factory efficiency finally works in construction’s favor.

The aim is not to replace every craft or regional factory but to add flexible manufacturing capacity that follows demand and lowers risk. Builders and investors get faster schedules, predictable qualityand capital that sweats harder. In this model, the factory becomes an integral part of the product, signaling a more adaptive approach to building production.

Nick Durham is a General Partner at Shadow Ventures, a venture capital firm focused on investing in frontier technologies for the built world. This article was originally published at ThesisDriven.com