Cross-laminated timber is a viable and natural partner in the repurposing of old buildings as multifamily housing.

- In addition to its value in new construction, cross-laminated timber (CLT), is also a good solution for the adaptive reuse of old and historic buildings.

- The key benefit is the high strength/weight ratio of CLT panels and the stiffness they provide.

- CLT is a green alternative to demolishing and building new and offers biophilic benefits.

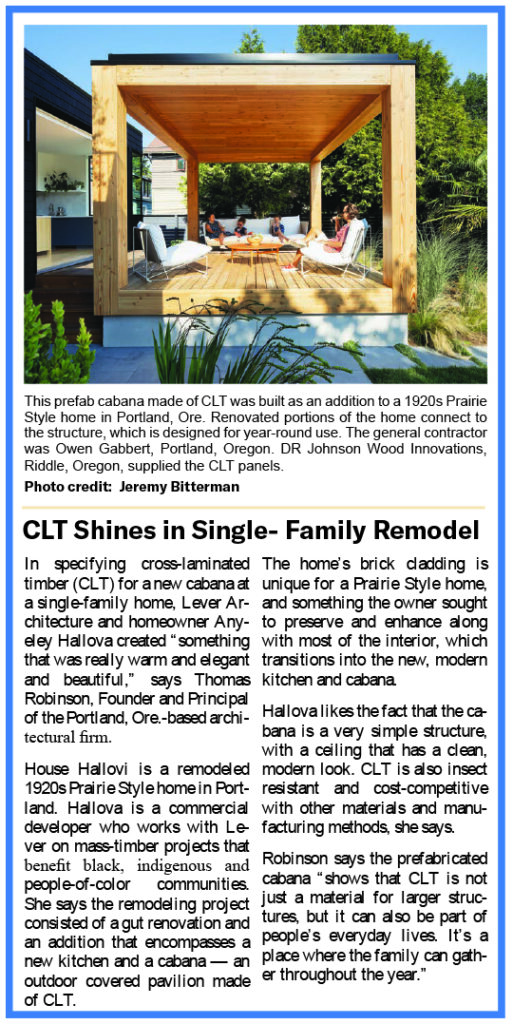

It has not gone unnoticed by builders and developers that CLT has a useful application in adaptive reuse projects. Offering strength, sustainability and cost competitiveness, CLT panels are being used in the restoration and renovation of historic buildings. Such projects are often welcomed as green alternatives to demolition and new construction. For the same reasons, CLT is also adaptable to single-family-home remodels (see sidebar).

Woven Into the Industrial Fabric

ACME Lofts is the result of the restoration and vertical expansion of a 3.5-story, 150-year-old, unreinforced masonry structure in New Haven, Conn. Andrew Ruff, Research Director for Gray Organschi Architecture, says CLT was significant in weaving the project into the industrial fabric of New Haven’s Ninth Square historic district.

Two floors of housing were added atop the existing building. The project includes a new CLT stair and elevator core and a two-story CLT honeycomb extension, with exposed CLT interior and exterior walls and ceilings. Designed to meet Passive House standards, ACME Lofts also contains 18 residential apartments, ground-floor retail, a gym, a bike room and a rooftop amenity space for residents.

Photo credit: ADX Creative

Photo credit: ADX Creative

The building served as the headquarters for the ACME Furniture business from the late 1980s until its closure in 2017. It originally had a brick exterior and timber interiors, but the timbers weren’t large enough to qualify the building as heavy-timber construction. “It was mill-building construction that didn’t really meet the contemporary building code,” says Ruff.

During the structural design process, Gray Organschi and the engineering team weighed their options. Light-frame wood wasn’t stiff enough and steel was too heavy; both would have required an enormous investment to reinforce the existing structure.

“From an economic perspective, the only way that this project could have been built at this density and preserve the historic fabric of the existing building was to use CLT,” Ruff says.

Developer Spiritos Properties, New York, N.Y., purchased the building with the goal of using mass timber on the upper floors. “They wanted to expose as much CLT as possible, and for the renovated building to be designed to Passive House standards,” says Dave Johnson, EWP sales manager for SmartLam North America, Columbia Falls, Mont., which supplied the mass timber. “Exposed wood is aesthetically pleasing and provides biophilic benefits to the inhabitants.”

Johnson adds, “Using CLT allows for complete offsite fabrication of the structural building components. This significantly increases the speed of installation compared to other building methods.” Also, due to the nature of an urban build, the quick installation minimizes the need for on-site storage space.

Ruff believes the real benefit is the high strength/weight ratio of the CLT panels and the stiffness they allow for in construction. “For ACME, we used CLT not only for the upper two floors, but also for the elevator and stair core,” he says. “We were able to concentrate a lot of the new load of the overbuild onto the timber core as it came to grade.”

The elevator shaft comprises two 37-ft. CLT panels stacked on top of each other. The first set of panels is entirely contained within the existing building. “They opened a hole in the floor, reinforced it, and a crane operator dropped the panels in vertically — basically blind — to connect it to the interior,” says Ruff.

Projects like ACME Lofts represent an opportunity for builders and developers in urban centers that were built 100 to 200 years ago, with many older, low-rise buildings. “Now [those properties] have been upzoned and the land value has increased,” he says.

Johnson says the project “breaks new ground for how we think about maximizing and improving use of an existing building by not limiting [ourselves] to how that structure was built. For example, ACME Lofts utilized CLT for the shaft material, which is often assumed to be Concrete Masonry Units..”

In Gray Organschi’s experience, CLT has proven to be a worthy partner in adaptive reuse projects. “It’s complicated on the design side and takes a crane operator with nerves of steel, but it’s proven to be quite effective to marry eccentric, difficult historic structures with large, engineered [wood] panels,” Ruff says.

Photo credit: Gray Organschi Architecture

Photo credit: Gray Organschi Architecture

CLT in Cream City

Timber Lofts in Milwaukee, Wis., is the city’s first mass-timber building. The project is in Milwaukee’s industrial loft district and includes the restoration and reuse of a five-story building, with a new four-story building immediately adjacent. The two buildings comprise a total of 60 residential units. The first floor consists of retail space, the resident lobby, a leasing office and a fitness room.

The original Louis Bass Building, constructed in 1891, was empty and in disrepair due to years of neglect. “Our developer, Pieper Properties, found this gem and gave us the pathway to adding on,” says Tim Wolosz, AIA, Principal at Engelberg Anderson Architects in Milwaukee. Wolosz says it was Pieper that had the foresight to use CLT.

The building is clad in Cream City brick. Indigenous to the Milwaukee area and revered by residents, the brick gets its yellowish-brown patina from the local clay, he says. Heavy timber framing was used on the interior.

The Bass building was granted historic status by the National Park Service, opening access to a $2 million grant for renovation. From the beginning, says Wolosz, the goal was to showcase the interior wood framing and integrate a new building that would be complementary.

Photo credit: Gray Organschi Architecture

Requiring large spans for the retail space, the first floor employs a steel post-and-beam structure with exposed CLT ceilings. At the residential levels above, the CLT spans from demising wall to demising wall of each unit. Five-ply panels were manufactured by KLH, New York, N.Y., in 5-by-18-ft. spans, allowing a single panel to span from unit-to-unit width (west to east).

The marriage of old and new added complexity to both the design and approval process, prompting Engelberg Anderson to define a contemporary architectural character for the addition. Rather than try to match the existing Cream City brick, the architects took inspiration from its rustic, sooty appearance for the dark charcoal masonry of the addition. At each floor, the addition punches into the existing building to create a continuous interior loop.

“The reality is that there is a lot to gain by offsetting costs,” says Wolosz. “For example, less interstitial space between floors translates into less exterior material, plus a reduction in components like resilient channels and insulation. When you start multiplying those savings by 400 sq. ft. [at Timber Lofts], you see the true cost savings potential of mass timber.”

Susan Bady is a freelance writer based in Chicago, Ill., who focuses on residential and commercial design and construction topics including sustainability and building technology.