Modular construction doesn’t advance by sudden revolutions. Instead, it evolves step by step.

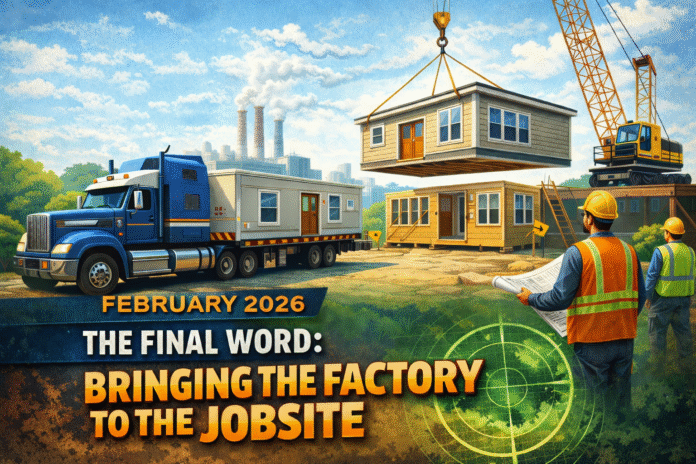

For decades, we’ve built modules in centralized factories, shipped them over long distances and set them into place with a crane. It’s a proven system with enormous efficiencies, but it has limitations. Transportation adds cost, complexity, size restrictions and scheduling risk; crane work brings its own challenges.

In recent years, however, I’ve seen something new emerging. Microfactories represent a fascinating shift.

Rather than assuming the factory must stay in one location, what if it could come to the project? Transportation would become a minor line item instead of a major cost.

Microfactories are designed with that idea in mind. They’re compact, automated, flexible and deployable. Some can be installed regionally, some can be positioned almost at the jobsite, and some can even move from project to project as demand shifts.

One company shows how robot-assisted lines can be built in smaller footprints. Another how containerized manufacturing units can operate anywhere. Proximity to the jobsite changes everything. Friction—and its associated costs— disappears.

Microfactories feel like a possible next step in the evolution of modular construction. We solved weather issues by moving indoors. We addressed labor shortages by centralizing talent. Now we are tackling distance.

If the factory doesn’t have to be hundreds of miles away, we can build modules larger than what highway travel permits. We can avoid multistate shipping fees, which often exceed $15,000 per unit. We can lower the risk of transportation damage and improve predictability. And we simplify project timelines because supply chains become shorter and more reliable.

Microfactories could also make it easier to explore technologies once considered impractical.

An idea that has fascinated me for years is the potential to perfect roll-off installation for single-story modular units. Today, cranes dominate modular setting, but cranes have specialized labor requirements, tight scheduling windows, expensive mobilization and limitations in dense urban locations. If we could refine roll-off systems so that modules could be placed with precision using hydraulic leveling, automated positioning, or self-adjusting carriers, the economics of modular could change.

A microfactory located near the project makes this idea more realistic. Shorter travel distance means less stress on the structure during transport, making roll-off placement more viable. It also reduces the need for oversized equipment.

Imagine modules being slid into position with millimeter accuracy. Imagine set crews working faster, safer and with minimal equipment. Imagine urban infill sites where modular placement becomes as simple as backing in a truck and guiding the unit into place. These are not fantasies. They’re engineering challenges that become solvable once distance is removed from the equation.

Microfactories will not replace centralized factories any time soon. High-volume regional plants will remain essential for large-scale production. But microfactories add something we have not had until now: a flexible, decentralized manufacturing model that brings the product closer to the need. They offer speed and adaptability. They reduce the burden of long-distance transportation. And with them comes the real possibility of building without cranes.

We are in the early stages of this trend, but it deserves attention. It may well define the next decade of offsite construction. For those of us who have spent our careers pushing the modular industry forward, it is exciting to imagine where this path might lead and how much more efficient, accessible and innovative our building systems can become.

If you liked this article, you can follow Ken Semler on LinkedIn, where he offers daily insights and commentary about offsite construction.

What if manufacturing could occur close enough to the site so that transportation becomes a minor line item instead of a major cost?