Rise of the Machines: Jobsite Edition

These robots are redefining what it means to ‘go offsite,’ by bringing automation, precision and endurance to the field.

Although Offsite Builder magazine primarily focuses on prefabricating homes inside factories, some innovative companies are bringing the factory to the jobsite. They’re doing it with advanced robotics. Here, we’ll look at examples of four very different jobsite robots. They lay bricks, plan layouts, drill holes in concrete, finish drywall and paint.

Hadrian’s Walls

Mark Pivac is the CEO of FBR, which is headquartered in High Wycombe, Western Australia and specializes in building autonomous robots that operate in uncontrolled environments. The company also has a business development office just outside of Miami, Florida.

Like other trades, bricklaying is suffering a labor problem: Few young people are interested in doing it. Furthermore, “There’s a huge dropout rate in training programs for bricklaying,” Pivac says. “Even though it’s a very well-paid trade, students lose interest after discovering how physically hard it is. There’s a lot of repetitive strain injuries and skin problems.”

A challenge for developing a bricklaying robot is making it big and strong enough to move the blocks around, but also accurate enough to place them with precision. Pivac invented the technology to manage this feat and incorporated into FBR’s Hadrian robot.

The first requirement for a bricklaying robot was that it had to be mobile and quick to deploy on-site. Pivac says, “We went for a boom solution, which folds up for transportation and unfolds quickly on the jobsite.”

However there’s a problem with a long boom: it can bounce around with the weight of the block and the wind pushing on it. A bouncing boom can’t accurately place a block.

Pivac invented a control system to compensate for this. “The control system has two parts. One positions the end of the boom approximately — within, say, a foot of where it needs to be. And then a very fast, dynamic and highly accurate robot at the end of the arm does the final positioning. The trick is measuring the position and orientation of the end of the boom and having that very fast robot at the end make rapid adjustments, so that it puts the brick in the correct location, even as that boom is continually moving around.”

For this system to work, it needs to make fine adjustments rapidly enough to keep up with the moving boom. “You need very powerful motors to make sure that everything moves fast enough.”

FBR primarily acts as a masonry subcontractor to Gcs. “We call it ‘wall-as-a-service’ because, ideally, we partner with material suppliers so we can build with bigger blocks that are optimized for robots rather than humans,” Pivac says. Although the robot increases efficiency when it uses regular-sized blocks, using bigger blocks is even more efficient.

FBR has found that some Gcs are interested in buying their own Hadrian robot. “That would make sense for a GC building a few hundred homes a year — enough to keep a Hadrian busy. It can build approximately one house per day.”

Using the robot also enables parallel processes. Because the robot operates from CAD files and is highly accurate, any prefabricated components — such as roof trusses and

bathroom modules — can be guaranteed to fit. There’s no need to wait until the bricklaying is done to get started on prefabricating those elements.

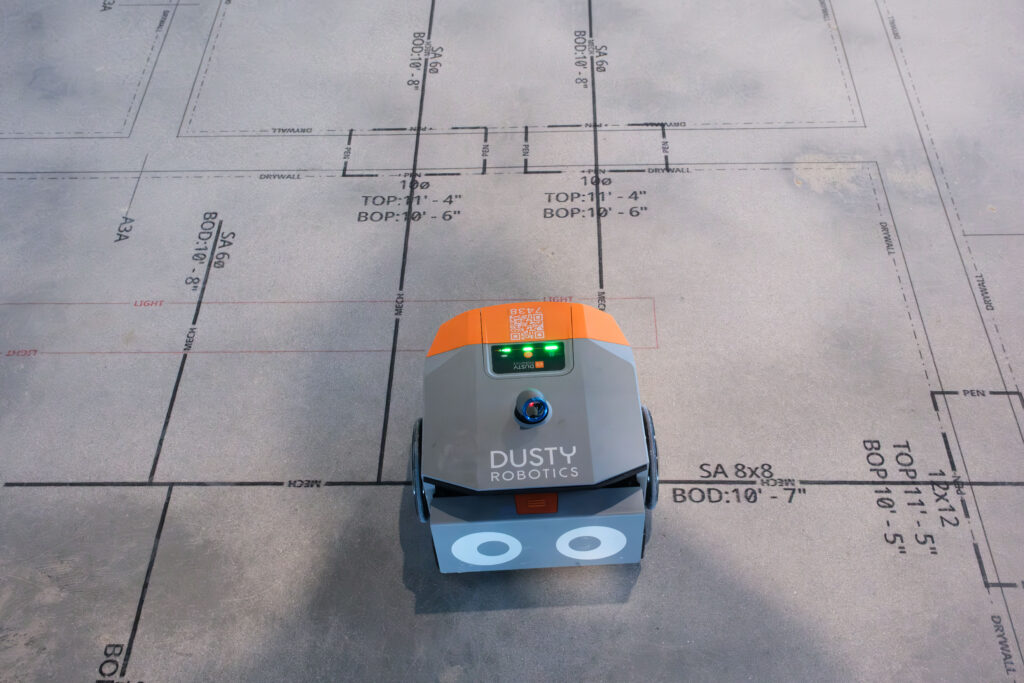

Automated Layouts

Dusty is a robot that looks a bit like a chunky Roomba vacuum cleaner. It’s an alternative to manually laying out building plans with chalk and string. Dusty takes everything in a building’s digital model and prints it at 1:1 scale directly onto the concrete floor,” says Zachary Reiss-Davis, Senior Director of Marketing at Dusty Robotics, which is headquartered in Mountain View, California.

The company leases the FieldPrint Platform — the robot and its software — to customers on a usage-based pricing system. This means that customers “pay only for the days they use the system,” Reiss-Davis explains. There’s no need for Dusty to provide a robot operator. “We pride ourselves on the ease of use of the system and our customers operate it themselves,” Reiss-Davis says.

The Dusty robot has been used all across North America on many different types of projects “from affordable housing developments to hospitals and from data centers to tilt-up construction warehouses,” Reiss-Davis says. It’s less appropriate for a very small project — such as a single-family home — where it might be overkill. Also, “If a project doesn’t have 2D or 3D digital models in a product like AutoCAD or Revit, a contractor would need to make them before they can use automated layout.”

As well as printing the layout of the walls for the framing crew, the robot can simultaneously print the layout for other trades, with the goal of increasing coordination and reducing jobsite conflicts.

Manual layout is prone to human error, especially with a less experienced crew. And it can be hard to find an experienced crew. Reiss-Davis says, “Construction delays and rework are routine on most jobsites,” but by using the robot to translate digital designs directly to the jobsite, Dusty’s customers “find that we’re consistently five to 10 times faster than a two-person layout crew doing manual layout, and we maintain 1/16” accuracy.”

As well as being reliably accurate — thus reducing rework and its associated costs, “Dusty is usually less expensive than manual layout, when you factor in the total labor hours required in both cases,” Reiss-Davis says.

Easy Anchor Bolts

CSC Robo’s global headquarters are in Hong Kong, with US operations based in Long Beach, California. Its Drillcorpio robot has been commercially available in the Asia-Pacific region since 2023 and has been used on over 30 commercial jobsites. “We’re currently launching in the US, with early interest from top 50 contractors and rental groups,” says Sandra Grigoletti, the US Sales Director.

The company has developed two robots that “automate the drilling of anchor holes into concrete, which is a physically demanding and repetitive task common on almost every major construction site,” says Grigoletti. Both robots can drill into flat, curved, or angled concrete surfaces.

Drillcorpio Df is a self-navigating robot that’s “capable of drilling into floors, walls and ceilings up to 9.5’ high. It moves itself into position, aligns to the desired drill location, adjusts to the right angle and drills automatically. Then it moves on to the next location,” Grigoletti explains.

The D3 version of Drillcorpio “mounts inside a scissor lift basket and can be used for overhead or wall drilling. It not only drills holes, but also installs anchors,” Grigoletti says. Both robots can be used with or without BIM files.

To operate without digital files, the robots “use their 3D camera and AI to identify physical marks on the drilling surfaces — like an X written by a human, printed by a BIM printer like Dusty, or projected by a Robotic Total Station or line laser,” Grigoletti explains.

The robot’s ability to operate from visual markings “makes it accessible to most construction projects, rather than only projects with extensive BIM efforts,” Grigoletti says. However, if BIM is used, the robots have additional capabilities, including self-navigation on the Df model.

The company operates in three ways. It sells the robots to contractors and CSC Robo trains the contractors’ crews. It also rents the robots on either a weekly or monthly basis. And, finally, “We support trial deployments with qualified contractors to prove ROI before full commitment,” Grigoletti says.

The problem CSC Robo addresses is that manual concrete drilling is not a great job for humans. It’s a labor-intensive and fatiguing task that involves vibration, dust and noise, plus it carries the risk of repetitive strain injuries. Robots are also able to maintain consistency better than humans — drilling to the perfect angle, depth and spacing with no over drilling and subsequent rework. This is especially important on jobs that involve hundreds or thousands of holes. Robots can also maintain the same pace over long periods As Grigoletti puts it, “Humans slow down. Robots don’t.”

Perfect Finishes

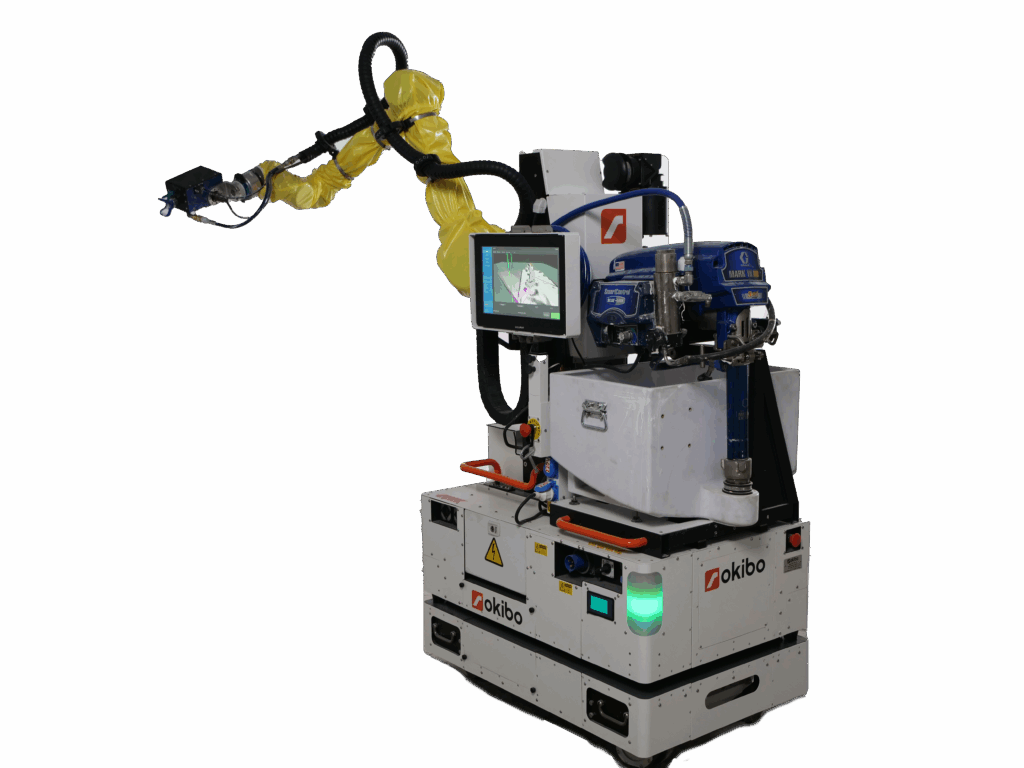

Okibo is headquartered in Petach Tiqua, Israel and has a US office in Englewood, New Jersey. They rent their drywall finishing and painting robots to either subcontractors who perform those trades or self-performing GCs.

They’re also responding to a shortage of skilled labor, while simultaneously providing a way to “improve efficiencies and reduce costs,” says Guy German, Okibo’s CEO. “Not only is there currently a shortage of labor, but also the trends point in the same direction. Construction workers are getting older. And, especially in wet trades, training takes time and getting good, qualified workers is becoming harder and harder.”

Usually, Okibo robots are rented on a long-term basis after a trial period but, in Germany, the partner Okibo works with also offers “short-term, project-based rentals.” German says the cost to rent the robot is in the range of “tens of thousands, less than one hundred thousand, dollars per year. You get a very fast ROI.”

After a few days of training, the robot is easy to use and requires no complicated set-up. “Similar to the app store on your phone, you choose the app you want the robot to perform, for example, drywall sanding. You attach the right tool on the arm — if you don’t choose the right one, the software will tell you — and then it’s simply a matter of putting the robot in front of the wall and making sure there are no obstacles in the way.” Once the robot is in position, it knows what to do, based on the options selected, such as the level of sanding.

“There are no files that need to be uploaded, and no markers need to be set. It has sensors that perceive the walls, and it gets to work immediately,” German says. Once

the robot’s finished one wall, including the corners, it’ll move onto the next one. It also handles ceilings easily, which for humans can be a painful experience.

Depending on the exact application, the robot can be many times faster than a human. For example, “Painting the ceiling of a huge parking garage with large spray tips, the robot was 16 times faster than a person,” German says. “On a project in the US, the robot was doing level four sanding five times faster than a professional human taper.”

The efficiencies gained ultimately depend on how effectively the robot is used. “If it’s waiting around because a room isn’t ready for it, then that’s less efficient than if it can do rooms one after another. Different customers get different value from the robot.” So, if the robot is going to be brought on-site, “You need to make sure that it will have enough square footage to work in, without obstacles, and without bottlenecks caused by rooms not being ready.”

The robot is so simple to use that “non-proficient operators can run the robot and get the same results as someone who’s used it a hundred times.”

This clearly contrasts with humans. German says, “A novice just learning the trade will do a poor job. But, over time, they get better and eventually will become an expert. But then they retire, and you get another newbie who doesn’t know the job. Robotics just get better and better until the end of time.”

Zena Ryder writes about construction and robotics for businesses, magazines, and websites. Find her at zenafreelancewriter.com.