How do you differentiate this technology from a fancy BIM?

For years, the phrase “digital twin” has been floating around conference stages, industry webinars and LinkedIn posts. It pops up so much that one might be excused for thinking it’s the silver bullet for construction inefficiency. Lately, it has become a favorite buzzword in the modular space.

Advocates call digital twins the “next big thing,” promising factories and developers’ real-time insights, smoother workflows and error-free projects. But here’s the truth: digital twin implementation in modular is far more complex than simply upgrading from a Building Information Model (BIM). And despite the hype, the pace to widespread reality has so far been a slow crawl.

What’s the difference between a BIM and a true digital twin? The answer is that most of what’s labeled “digital twin” today is just BIM with lipstick, and a longer lifespan.

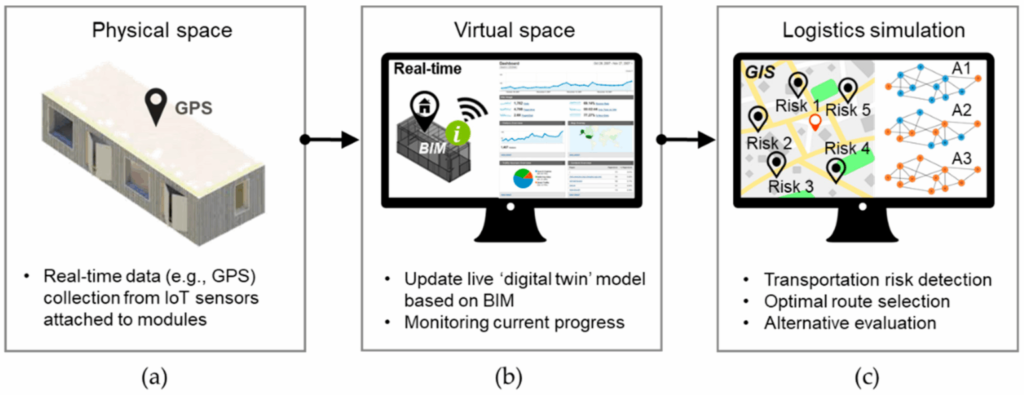

A BIM model gives you geometry and data about a building at the the time of design. A digital twin, if done correctly, lives on through the entire lifecycle. In modular construction, that means that each module has a unique, serialized digital identity — a twin — that carries its production history, QA results, logistics details, and later, operational sensor data.

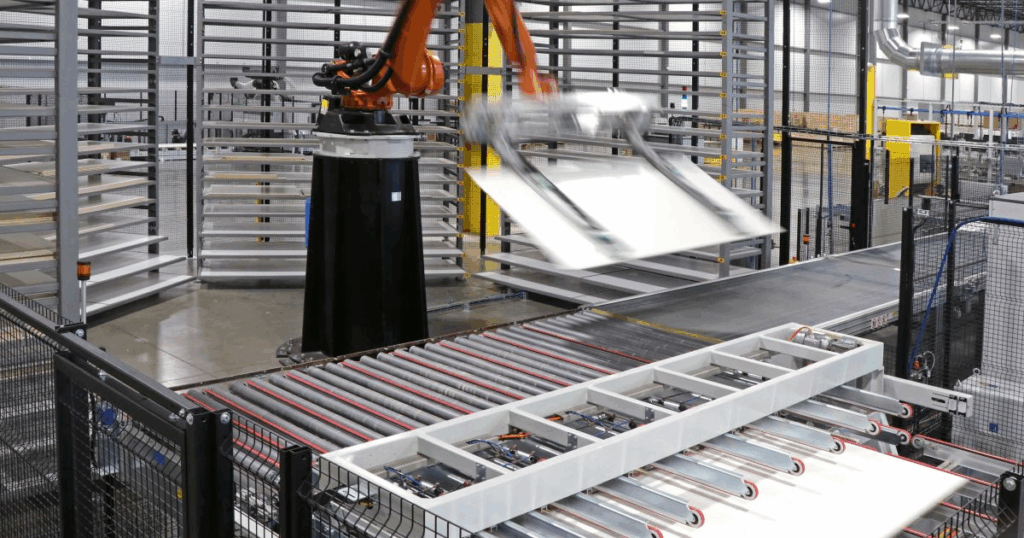

Creating something like that is a tall order. You’re not building one object but thousands of standardized, yet customizable, components. These components move through factories, are by trucks and are lifted by cranes into final assemblies. To qualify as a twin, every single step must feed data back into the model.

Real-Life Examples

Despite these challenges, however, there are real examples of digital twins. They’re just not yet visible on mass scale.

DIRTT (North America): For years, this interiors company has been feeding design data straight into fabrication lines. Clients can walk through a digital twin of their future space, as well as of every panel and connection detail.

PT Blink (Australia): This company’s “design–manufacture– integrate” workflow drives multistory projects directly from a digital core. On a recent Brisbane project, the structure of a seven-story building was erected in eleven days. That’s twin-like execution: logistics, assembly and scheduling driven from the model.

Modulous (UK/US): Their TESSA software embeds a digital twin of their kit-of-parts system. It allows developers to configure housing layouts, test cost and schedule impacts, and then manufacture the standardized units. Each module carries its twin through the process.

Windover Construction (US): Using Autodesk Tandem, they hand over a functioning digital twin to building owners, linking IoT data to prefabricated assemblies. The twin becomes available to the building’s operators.

These aren’t lab demos — they’re revenue-generating products. But they also prove just how varied the “twin” definition can be. It depends on where you sit: design, factory, logistics, or operations.

Modular Adds Another Layer of Difficulty

In traditional construction, one could think of a building as one giant object. Modular complicates this because it produces three nested twins:

- The factory twin: This includes data on the machines used, the takt times and the throughput metrics.

- The product twin: Every wall, module, or cassette comes with its own QA and production history.

- The building twin: This is the assembled project with all modules mapped and operational data streams attached.

Each level must connect to the other two. For instance, if a plumbing chase in a module fails an inspection on the factory floor, that data should ripple through to the building twin for future maintenance tracking. Very few systems today do that seamlessly.

Even in countries pushing the envelope — Singapore with its PPVC regulations and national digital twin program, or the UK with platform DfMA strategies — you see more progress at the asset and city level than in the modular factory itself. The dream of a “factory-to-building-to-operations” twin is real, but it’s fragmented across multiple software vendors and workflows.

The Danger of Overpromising

Factories love to pitch digital twin capability. But investors and developers need to make sure they show the following:

- A unique digital ID for every module

- Data that flows from design through QA and logistics?

- An operations-ready model that can be handed over to the building owner when the project is complete

If they can’t deliver these, then what they’re really selling is advanced BIM. The word “twin” gets slapped on proposals to sound future proof, but behind the scenes, many are still working off PDFs and spreadsheets.

Where We’re Heading

Industry analysts agree: the trajectory is toward integrated twins. Research in 2024–2025 frames modular digital twins as “emerging practice,” not established norm. Startups are racing to close the gap — linking IoT sensors in factories, embedding RFID in studs, or feeding QA scans into module databases.

The reality is that digital twin success in modular will require standardization across the entire supply chain. Factories, transporters, crane crews, inspectors and owners will all have to trust the same platform. That’s a heavier lift than just buying new software — it’s a cultural shift.

The digital twin in modular construction is no longer just a concept, but it’s not yet the plug-and-play solution many headline writers want you to believe it is.

Pioneers of this technology — DIRTT, PT Blink, Modulous, Windover — are showing its possibilities, but also its complexity. Until factories can connect the dots from the production floor to the long-term asset, modular’s “next big thing” remains a work in progress rather than a fully proven reality.

Gary Fleischer is Editor-in-Chief of Offsite Builder magazine.