This startup has found success by avoiding the mistakes of previous failed ventures.

• BotBuilt is currently manufacturing basic wall panels, but plans to add a more finished product. Their customers include custom builders and a top-20 builder.

• They save money by purchasing used robotic equipment that’s not accurate enough for auto manufacturing, but more than adequate for structural framing.

• When designing their robotic system, they prioritized the ability to handle different designs, rather than to quickly produce the same one over and over.

BotBuilt was founded in 2020 and is headquartered in Durham, North Carolina. Their website claims that they are “Revolutionizing construction with flexible robotic systems and transformative technology.” So, you might be forgiven for suspecting this is a bunch of ‘tech bros’ thinking they will ‘disrupt’ the construction industry with truckloads of venture capital and what they probably like to call ‘bleeding edge’ technology. But you’d be wrong.

BotBuilt Co-Founder and CEO, Brent Wadas says that his company has studied Katerra’s mistakes and aims to avoid them. Rather than disrupting the construction industry, they’re working to fit into it as seamlessly as possible.

What follows is a conversation with Wadas about BotBuilt and what it hopes to accomplish.

Q. None of the founders of BotBuilt have experience in construction. Isn’t that a liability?

Yes, but we have a board of advisors with the necessary expertise and experience, and we spent the first year or so of our company’s existence listening to and learning about the industry. We learned from custom builders who build five homes a year and from companies like D.R. Horton and Lennar, which each build tens of thousands of homes a year.

We’ve come to understand where their needs are being met, and where they aren’t. We’ve learned that the custom builder who’s building on-spec for a multi-million-dollar home has vastly different expectations and needs than, say, the multifamily builder or the top-20 builder.

For instance, the latter’s goal might be to be the cleanest, greenest big home builder in North America. What they love about our system is that it figures out exactly what to buy, where to cut and how to place it in the most efficient manner so we end up with only a trash bucket of waste versus the gigantic dumpster they’re used to.

We want to adapt to the culture of construction, not come in and tell people “We’re smart tech people and know better than you and this is the way you need to do it.”

For us to assume that we somehow know better because we have robots would be asinine. We wanted people to advise us on every feature of the industry, not just from a business P&L standpoint, but from a cultural standpoint. We wanted to understand how we can improve the lives of those in the industry. Then we do take a scientific approach to it and figure out how we make the technology work in that paradigm, and hopefully improve that paradigm over time.

To say that we’re going to come in and revolutionize everything once and for all would be gigantic hubris and also, quite frankly, a precursor to our downfall.

Q. Will BotBuilt manufacture framing, complete wall panels, or volumetric modules?

We’ve started with unfinished wall panels. They include the framing, exterior sheathing, window and door openings. The reason we started here is that there’s high demand for panels, which speed up construction. Builders want a quicker way to turn a patch of dirt into a mortgageable product that someone else is paying the interest on instead of them. And these wall panels are an easy way to help achieve that.

Demand is through the roof; there’s more demand than we have the capacity to keep up with. And it was easy to slip our product into the market. The developer and builder don’t have to do anything radically different. They need a smaller framing crew, and the framing can be done more quickly on-site than conventional framing. There’s also a low-risk entry point: a developer can have us manufacture the framing panels for one single-family home and see how it goes.

But we don’t plan to stick at that low level of finishing. We want to build more complete and finished products that are still easily shippable. We don’t envision doing volumetric modular in the near term — largely because of the more challenging transportation logistics — but who knows about the long term?

In terms of cost our product is pretty much on par with traditional stick-building right now. But I expect costs to come down in the long term, as more companies start producing more homes and the supply of new homes increases.

Q. What are you currently building? And what do you plan to build in the future?

We targeted single-family residential first because it was the easiest market to learn in. It would be much harder as a new company to step into a massive multifamily project with numerous stakeholders. And we’d have to bid on projects and be chosen ahead of other suppliers.

Single-family homes are also the hardest technical problem because we’re using stud-grade lumber. We had to develop computer vision systems that could get bowed or bent lumber to work straight. If we’d gone into commercial or over four-story multifamily, we’d typically be using steel or CLT, which is much straighter and much easier and more predictable for robots to work with. Also, there are many small developers who are willing to try something new on a smaller project.

Now that we have some experience, we’ve started running multifamily and commercial buildings through our software, which takes 2D designs to 3D and figures out how to panelize designs in an optimal way. So, we know the software’s capable of doing it and we know the hardware can do it, because robots have been building with steel for decades.

Q. How many projects have you completed?

As of November 2023, about 10 single-family homes, with a few more on the go. We started building in 2022 and got to know, at the level of the jobsite, what would improve the lives of the framer, the builder and the customer — to understand where we were adding value and to double down on those areas.

We’ve completed a few semi-custom tract houses and we’ve also built a couple of fully custom, multi-million-dollar homes down by the lake in Pinehurst, North Carolina. We just started working with a top-20 builder.

Q. How quick are the robots compared to people?

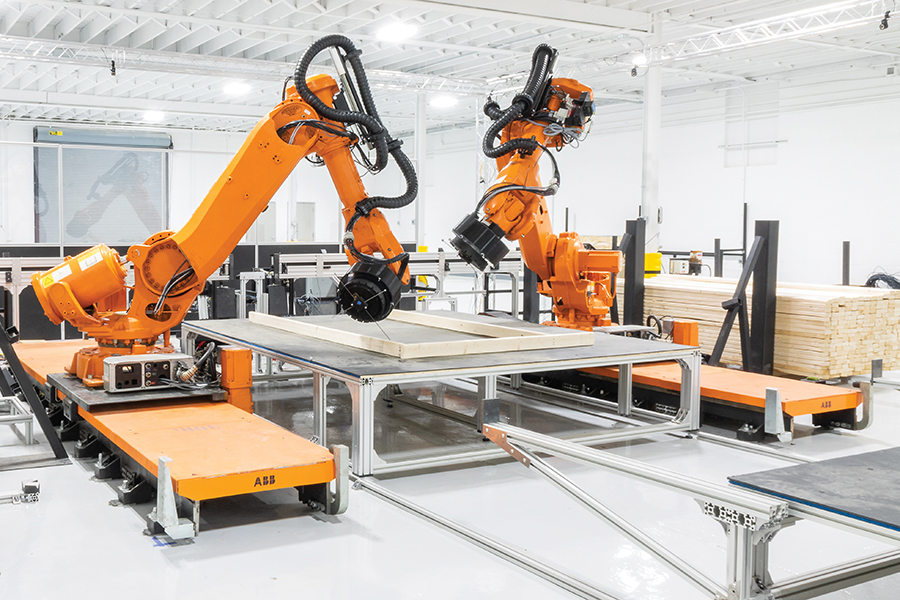

If the lumber is precut and arranged in a row, a robot team is only slightly slower than a human team. Two robot arms working together are what we call a team, compared to a typical team of four to five humans in a panel factory.

Although a team of humans vs. robots might result in the humans making it a pretty close race, after an hour or two, the robots are far faster and more efficient, not needing to slow down, take breaks, or have time off. Not only can the robots work continuously 24/7, but they also can work for about $1.40 an hour.

If the robots start with raw material and they have to cut and place the lumber themselves, it’s significantly longer. However, suppose you put two robots together and they both have access to the same tool belt, as we call it — the free nailers, the stud plate connectors, the saws, and so on. Then you have 10 of those robot pairs working together, they could easily put out a house or two of these panels in a couple of shifts.

But speed at the manufacturer’s end doesn’t matter to the developer or builder. They need time to get the foundation ready and to get all the permitting done, so there’s no rush for us to complete the panels. Where they need speed is in the erection of the panels. When using panels, they can frame a house in a few hours with a small team instead of a few days or weeks, depending on the size and ability of the on-site framing crew.

Q. Can you tell us more about your robots?

From 2021 through 2022, we explored the technology options. We needed to figure out what technology is needed for business profitability. We wanted to know what type of robotic systems we could use at the lowest possible cost with the greatest optimization. And what software systems could communicate with those robots so that we can build more designs with automation.

Robot arms used in the auto industry are built to last, with very little maintenance. For car manufacturers, it’s often easier and faster for them to buy new robots each year, rather than recalibrate old ones. We purchased some robots from an auto factory that needed their robots to be within 0.2 millimeters of accuracy. That’s overkill for single-family residential construction, where an eighth of an inch makes you a hero. So, if a used robot is operating at 0.3 millimeters, we can buy them at a fraction of the cost of new and they’ll work perfectly for our needs.

There are lots of companies whose entire business function consists of going around to auto manufacturers, asking when their crop of used robots is going out, buying all of them, refurbishing and painting them, and selling them on eBay.

We currently have four robotic systems and will likely acquire about 10 more in 2024. A system is two robot arms, the tracks they run on, all the cabling, the computer systems and the custom tooling we build here in our factory — all the tools required to complete a wall panel with sheathing and routing near the arms so they can switch out quickly.

A robotic system would cost between $360,000 to $500,000 if bought new. When we buy used, they vary between $90,000 to $200,000 at the next-to-new top end.

Q. What do you see as Katerra’s major mistakes?

People can be very, very good at fundraising but that doesn’t mean they’re good at creating a sustainable business that makes a profit. I don’t know if that was one of Katerra’s problems, but I personally believe in very cautious fundraising. I don’t want us to bang the fundraising drum, bring in tons of cash and have us get lazy about what we need to do as a business, how we need to address market needs in cost-efficient ways. We also didn’t want to give too much control of the company away to investors.

When you raise a lot of money, it’s all too easy to feel like you’ve won something — even if you haven’t built a home that anyone actually wants to buy. I don’t want to be one of those founders who has an ability to golden tongue our way to millions of dollars but not produce something that people actually want to buy. We did fundraise and accept outside investment early on to get started, but we’re not fundraising currently. We’re just working on getting product out the door.

Katerra had the business model of buying up companies with different areas of expertise and hoping they could all play together. But the systems and the software weren’t immediately compatible. They had disparate teams doing disparate things with disparate tech. That makes it very tough to streamline processes and codify a standard operating procedure. Vertically integrating by acquiring companies is fine, but it works best if you can efficiently bring all the resources under one tech umbrella.

Q. What else did you learn from Katerra’s example?

Some of Katerra’s head engineers and technical leaders were very gracious after the company went under and met with us to talk about the costs and implications of changing designs. They said it would cost $500,000 to a million dollars to change a panel design.

So, we rejected the path of speedy repetition of one design — having robots produce the same product over and over — along with the inherent risk that costly changes to that design would be required. Instead, we chose flexibility.

Flexibility is important in construction. Much more than cars, buildings vary a lot within the same region, and different regions have different needs, too. [For example, a residential building in downtown Los Angeles, Calif. is very different from a residential building in rural Florida and their needs are different with respect to things like wind load and earthquake resistance, as well as aesthetically.] So, to serve a broad market, we wanted flexibility.

We looked at what low-cost, off-the-shelf robotic technology is currently available and adapted new tooling systems and developed software that enables that hardware to build any type of design rapidly. People often think of robots as doing the same thing again and again. And robots can do that, but they don’t have to. Instead of taking months to re-design, re-engineer, re-plan and re-stamp a single design, we instead allow the robots to exercise the flexibility they’re capable of.

Zena Ryder writes about construction and robotics for businesses, magazines, and websites. Find her at zenafreelancewriter.com. All images courtesy BotBuilt.