A conversation with Nolan Browne of ADL Ventures

What role will industrialized construction (IC) play in our industry in coming years? Nolan Browne believes it will be a big one. Browne is a Founding Partner at ADL Ventures, a firm with six locations across the US that helps launch and grow IC firms and business units. He calculates that, currently, between 2% and 5% of construction is industrialized, but he predicts a future where that grows to 20%, then 50%.

Even a smaller amount of growth would be impressive. For instance, the Association of General Contractors (AGC), estimates that the industry builds nearly $2.1 trillion worth of structures each year. “If just 8% or 10% shifts to IC, that’s many billions of dollars,” says Browne.

If Browne’s projections are correct, the question is how will your company fare when IC becomes more common? Is it set up to profit from the transition? We recently asked Browne a series of questions about that topic.

Photo courtesy of Nolan Browne

Q: How do you define IC?

A: It’s the application of advanced manufacturing principles to the art of construction. Construction doesn’t have to be done in a factory — the location doesn’t matter. What matters is that IC practitioners use manufacturing processes, which are repeatable, scalable and subject to economies of scale. They also need to incorporate learning and improvement over time, which lets them drive costs down and drive quality up.

Q: What is the first step a traditional company should take to transition to IC?

A: The first step is to identify your special skill sets or capabilities, your ‘unfair advantage(s),’ as well as your weaknesses. You want to build on the former and shore up the latter.

For example, half of the C-suite people at one of our building product clients have a manufacturing background. That’s their unfair advantage. By contrast, most construction company C-suites are strong in traditional construction disciplines (such as development, project management and regulatory requirements), but not in manufacturing expertise.

If you don’t have anyone on your team who knows anything about manufacturing, how much would you have to invest to get that expertise? How much time would it take?

Q: Are the steps to IC specific to each company, or do they differ?

A: Every local market is different, with various zoning and building regulations, material and labor costs, which means that companies tend to develop their own ways of doing things. At a very high level, though, there will be commonalities.

If a modular company is basically doing traditional construction under a roof, it’s likely that it can increase revenue just by laying out its lines [more efficiently] — so that input and output flow better— and by properly running those lines.

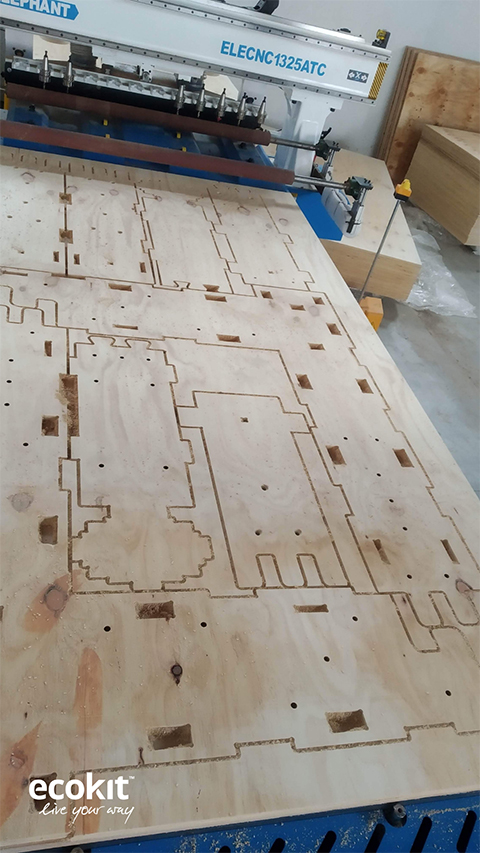

Photo courtesy of Ecokit

Q: How can IC companies handle the tension between needing to manufacture standard products, and owners’ desire for customized results?

A: If you go all custom, you’re not going to industrialize; it won’t work. But if you don’t customize at all, you probably won’t sell much.

However, you have to think about customization differently. Suppose your product has 12 or 15 different pieces or components. The components themselves can’t be changed, but the layout of how they fit together can be. Maybe a customer can’t choose how the electrical lays out, but they can pick the façade.

This balance is hard to do, and nobody has [been completely successful with it]. However, Module in Pittsburgh, Pa., Agorus in San Diego, Calif., and Remo Homes in Los Angeles, Calif. are thinking about it the right way and are all in different phases of making it happen.

Q: Is ADL doing anything to help companies make this transition?

A: At ADL Ventures, we’re setting up a demand aggregation program where we will have a standard product for sale to big developers. These are huge clients who’ll buy thousands of units at a time. We’ll have the supply chain in place — a network of independent manufacturing affiliates [of different sizes]. We’ll ship those manufacturers the materials and design blueprints and will pay them to manufacture what we need.

Let’s say the network needs to produce 2000 units that a developer has agreed to buy. One manufacturer might be able to produce 10, while another produces 100, and yet another produces 1,000. The point is that being part of a network allows even small manufacturers to participate in deals with large customers.

In addition, producing 10 standardized products is going to be more beneficial to the company than producing 10 custom projects.

Photo courtesy of Ecokit

Q: Is this demand aggregation model similar to franchising? And what are the costs involved?

A: In some ways it’s similar. For example, McDonald’s corporate sets the menu, they write the training guides, they have the supply chain, they design the layout of the restaurants.

If you have $2.5 million and a decent location to set up a McDonald’s franchise, then if you follow corporate’s instructions, you don’t need much else. All you need to do is show up and follow the instructions and you will make a return on your investment.

In construction, investors also want a return on their investment. If being part of a network means that you don’t have to worry about business development and securing projects, that you’ve got an off-take agreement (a buyer that has agreed in advance to buy your products), and there’s good demand, why wouldn’t you invest [in what’s needed to be part of that network]?

To be clear, though, we’re not franchising. Franchisees pay for the right to use the McDonald’s system. We’re not asking for payment; we’re just recruiting a set of reliable partners who want to be part of the system we’re laying out. As they get more efficient and profitable in their own factories, the profit they derive will flow to their own bottom lines — making the relationship more like a partnership.

Q: If a company wants to get involved in this kind of network, what should they do?

A: They can get in touch with us at adlventures.com. We’ve been pretty quiet about this because we’re still in the early stages. But we now have a couple of demo projects underway that incorporate this model.

We won a project with the Economic Development Agency (EDA) in western North Carolina, and we’re also doing some work in Texas. These government-funded projects will demonstrate that the model works. They’re a dress rehearsal for the for-profit version we’re working on.

Photo courtesy of Ecokit

Q: Can you describe these demo projects?

A: The work in Texas is a three-year, HUD-funded project, which started at the beginning of 2024. A coalition of private, public and academic partners, led by the University of Texas-Austin, aims to engage in industry-informed research to influence HUD’s strategy for affordable and equitable housing in Texas.

The North Carolina project is for what we call “premium attainable” housing. We’re designing a premium product that will be mass-produced and thus have an attainable price.

We’re working with industry and academic partners. Our off-taker (the customer who has agreed in advance to buy the products) is the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. We’ll be working with them to design something that fits their needs, and that is also designed for manufacturing. Then, we’ll get the fabrication plants set up to produce that design.

We won’t own the factories; we just want the factories to be manufacturing to our standards. We have factory partners selected.

Photo courtesy of Mighty Buildings

Q: Apart from the expense, are there any good reasons not to industrialize?

A: The traditional reason is that the industry is cyclical. The factory owner generally doesn’t want to pay for expensive equipment that’s idle during downturns. Instead, when the construction market goes into a downturn, a factory owner can lay people off. Then when the market picks up, they can rehire.

But there’s a massive shortage of housing in the United States, which we’re decades away from filling. Industrialization enables you to produce lots of houses at the right price for the market.

Photo courtesy of Mighty Buildings

Cyclicality occurs only when your prices are too high. If your demand is sky high at a certain price point, then you should be thinking about how to hit that price point — rather than how to maximize prices. [That is, if there’s lots of demand for $200,000 homes, focus on meeting that demand, rather than on building $400,000 homes.]

But, sure, if I’m running a small fabrication plant [making relatively low-cost homes] and I have $10 million in equity, I’m going to be really worried about downturns.

However, remember that work in progress on a factory floor represents a tremendous amount of capital; you could have millions of dollars of work in progress. And that can be really scary, especially if you haven’t already sold it, because you’re tying up capital. If you’re building a bespoke product, that’s a super high-risk thing to do because if your buyer doesn’t come through, you’re sunk. But if you’re building components, fungible things that are interchangeable, even if your Dallas buyers back out, your Austin buyers might come through.

And if your business is part of a network like I’ve described, and you go under, your assets aren’t worthless. Your work in progress retains its value because the network can [sell, complete, handle, assume?] it.

Same with inputs [that is, materials and products]. If you have unique inputs because you’re doing custom projects, then [if the business goes down], those inputs are greatly de-valued. But if you’re using the same inputs as other manufacturers, then those inputs have value to those manufacturers.

Photo courtesy of Mighty Buildings

Zena Ryder writes about construction and robotics for businesses, magazines, and websites. Find her at zenafreelancewriter.com.