Unity Homes has developed a set of best practices for manufacturing and installing closed panels for high-performance structures.

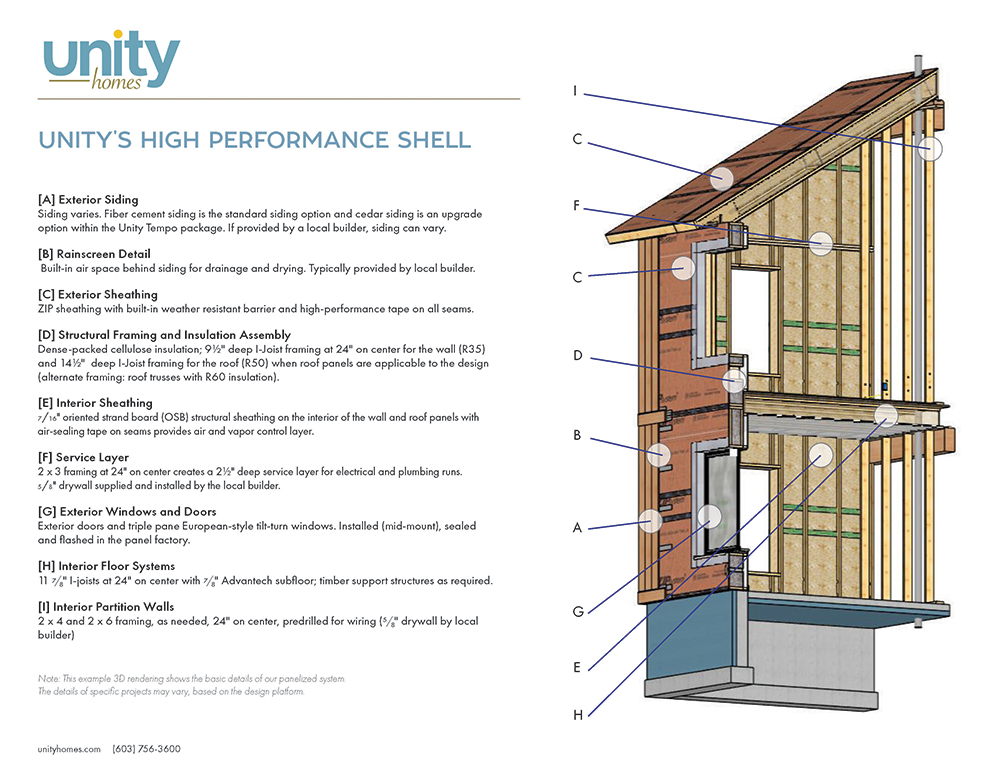

- Panels are built with engineered lumber and pre-insulated with cellulose. Finished homes offer high R-values and low air leakage.

- The company controls costs by using automated processes where they make sense, and by a commitment to continuous improvement.

- Homes and components are designed on a strict dimensional grid, which Unity hopes to make an industry standard. To further that goal, the company has launched a new software platform.

Walpole, N.H.-based Unity Homes (Unity) could be at the cutting edge of component-based construction. At the very least, they’re showing its potential and their experience may offer lessons to other manufacturers.

Wall panels are usually considered a commodity, but this prefab company has found success building high-quality homes that sell at market-average prices using panels with value-added features —engineered lumber, Zip System sheathing, and pre-installed installation, doors and windows.

Unity manufactures the panels, then sets them on the foundation or slab. The same workers do both, rotating between factory and field. Local GCs and subcontractors finish the homes.

The company received a flurry of press coverage in 2018 when it opened a 110,000 sq. ft. manufacturing facility in Keene, N.H. Around the same time, it also announced a joint development agreement with CertainTeed. Unity would help CertainTeed develop their One Precision Assemblies closed panels, and CertainTeed would help Unity develop a new software platform. (More on that below.)

The joint agreement ended in January 2024, but Unity has continued to grow its business of building prefabricated, high-performance homes.

Closed panels seem like a good idea to me, as more of the work is finished in the plant than with open panels. They’re also more easily transported than volumetric modules and can be easily placed on difficult sites. I’ve always wondered why more manufacturers don’t make them, so I decided to drive up to Keene and take a look at what Unity is doing.

Price and Quality

Unity is a brand of Bensonwood, which was founded in 1972 by Tedd Benson and his late brother. The company quickly built a reputation for high-end timber frames and, over the years, gradually implemented 3D modeling, CNC manufacturing and other digital technologies.

Home prices vary. Some of Unity’s models are priced in the $600,000 to $900,000 range according to the company website. Its entry level product — an ADU with 650 to 1000 sq. ft. of floor space — can be completed for $300,000, “in some areas.” That’s toward the upper end of the scale (BuildGgreenNH.com estimates ADU costs at $100,000 to $350,000 for that part of the country), but Unity says that buyers get a lot more than with a similarly priced stick-built home.

That “more” includes a high-performance building envelope. Finished homes have R-35 walls (compared to a code minimum of R-20) and R-50 roofs. The shell is blower door tested before being turned over to the local GC and, according to Mark Hertzler, Unity’s Factory Manager, 95% of homes score less than 1 ACH/50 (80% of them score less than 0.6). Windows are triple-pane models. If the homeowners contract with a local solar company to install solar panels and a backup battery, the structure can be essentially self-sufficient.

Cost-Effective Automation

Readers of this magazine will be interested in Unity’s manufacturing operation. Benson says that the company has put a priority on reducing costs, and that effort has included automation, repeatable designs and Lean manufacturing.

When I hear the word automation, my mind imagines something akin to Autovol, the Idaho prefab company known for its use of industrial robots. However, that’s a misconception; in fact, the Keene factory didn’t have a stereotypical bot in sight. The truth is that robots are very expensive and few companies generate enough revenue to justify the cost. There are plenty of less-sexy choices, and automation’s worth isn’t its wow factor, but its cost effectiveness.

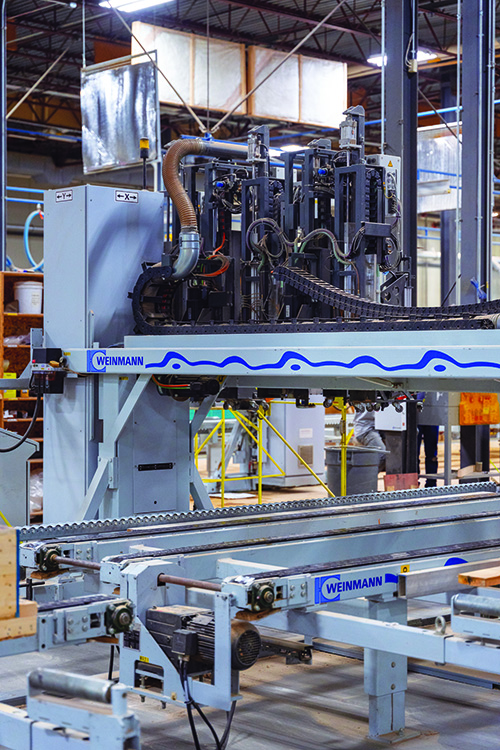

The shop floor of the Keene factory is a collaboration between humans and machines. For instance, workers place I-joist studs on an automated table between the top and bottom wall plates; the table creates the 2 ft. spacing and nails the studs to the plates. Workers place sheathing panels on walls; a multi-bridge nailer drives fasteners at the needed spacing and an automated router cuts out window and door openings.

An insulation machine fills cavities with blown cellulose to the precise density needed — it must be dense enough to prevent settling during transport, but not so dense that you lose R-Value. “As a check, we take core samples and weigh them,” says Hertzler.

The machines take their instructions from a BIM model that has been created on the company’s CADWork software.

I asked Hertzler how common this type of automation is in panel plants. He said he has seen it more in Europe than in the US, but it’s not ubiquitous there, either. “Even in Sweden, which does the most offsite construction, you see a mix of automated and manual processes,” he says.

Unity’s policy is to use automation where it makes the most economic sense. The wall line is the most automated part of the factory: all homes use insulated wall panels, so that line has the highest volume of work. Roofs aren’t always panelized — a lot of homes use trusses purchased from a truss manufacturer — so the roof line is less automated.Window and door flashing is applied by hand. “I’m not aware of any machinery that’s able to do the flashing,” says Hertzler.

Most homes take less than a week to manufacture.

Pre-Defined Options

Technology is one way the company holds costs down; design is another. Hertzler says they used to build one-off homes, but it wasn’t cost effective. “Our focus now is on repeatability and predictability,” he says.

Because most customers want at least some personalization, Unity has settled on an approach that falls between stock and semi-custom. It has a portfolio of standard floor plans but allows changes within strictly predefined parameters.

“We’re product based,” says Hertzler. By that he means they can offer fixed pricing by using a menu of predesigned elements that the factory and supply chain are set up to provide. Predesigned modules include first floor bedroom suites, mudroom connectors between the house and the garage, the garage itself, as well as front porches. “These can be added to a core design,” says Hertzler. If customers want something not on the menu, it becomes a custom home with a custom price tag.

Benson says that the goal of making everything predictable has been a guiding principle since he founded the company, and that doing so has created a smooth-running operation. “A lot of builders allow customization from an infinite series of possibilities,” he says. “There’s no logic to it. Nothing can be pre-designed or pre-manufactured.”

What choices do customers end up having? The variations result in roughly 30,000 possible unique homes. People who have bought a car recently should understand this: for instance, Ford claims that its F150 pickup has a billion possible configurations using standard options, yet the basic chassis doesn’t change so the factory can be highly automated and efficient.

Strict Design Grid

A big part of that predictability is what people at Unity call “The Grid.” It’s the dimensional parameters into which every design and every product must fit. “When we lay out a floor plan, the interior dimensions are based on a 2 ft. grid. Stairs and other heights are based on a 3 mm grid,” says Hertzler. Plans can expand or contract by those increments, and those increments only.

The grid also defines where studs and joists are located. “That makes it easy for designers to place everything from windows to plumbing drains,” says Hertzler. “It makes everyone as efficient as possible.”

It’s important to understand that this is an interior grid; the shell wraps around it. Panels must conform to the grid horizontally but can be different thicknesses. “We’re not worried as much about the exterior dimensions because they vary with wall thickness,” he says.

Unity ensures that products and materials meet the grid’s requirements via a software platform called Seamless, which it has been developing for a few years. Seamless was launched in early 2024 as a separate company, with Unity as its first user. (Technical and financial help developing this software was what motivated the partnership with CertainTeed.)

Benson has a big vision for Seamless. He didn’t share many details, but the gist is that he wants it to become a standard. The thinking is that, if enough offsite companies adopt the grid, more product manufacturers will begin making products that conform to it. He says that some Unity suppliers are already on board.

If enough other suppliers join in, it could become a marketplace of sorts. “Seamless will be a place where you can buy components that fit together with the grid,” says Benson.

It’s an ambitious goal to say the least, and he believes it will take a minimum of five years before seeing results. As a first step, Unity has begun working with architects to help them start designing to the grid.

Of course, the gridconcept isn’t new: Kitchen cabinets are made in 3 in. increments, and ranges, dishwashers and other appliances are made to cabinet dimensions. If Seamless succeeds in applying this concept to whole homes, however, it could help reduce the homebuilding industry’s notorious fragmentation.

“Our industry is the Tower of Babel when it comes to communication,” say Benson. “But if everyone was working with the same grid it would save everyone a lot of cost.”

Photo credit: John Hession

Continuous Improvement

Like most successful manufacturers, Unity is building a culture of continuous improvement. The factory crew uses Lean Kaizen, and Lean consultants have been brought in to train the managers. There are also quality assurance processes for each station. And a third party verifies that the company is building to its advertised standards. “We’re always looking to optimize, with the goal of reducing cost and increasing value,” says Hertzler.

Costs are also saved by the intelligent use of materials. “We do a lot of recycling in the manufacturing process. There’s very little waste,” he adds. They even recycle the boat wrap used to protect components from the weather when being stored outside and transported.

The fact that the factory and site crews are the same people also eliminates potentially costly disconnects between plant and jobsite. Understanding exactly how components will be installed and finished on-site helps workers ensure a quality product that can be installed and finished in the most efficient and timely manner.

“It creates a feedback loop,” says Hertzler. “For instance, airtightness is important to us, so knowing how the planes fit together on-site helps the factory crew ensure that outcome.”

The bottom line is that Unity’s system offers enough customization that buyers can feel like they had a hand in designing their home. At the same time, it’s highly standardized and cost-efficient. And the whole company is set up to reinforce that balance, while also continually looking for opportunities for improvement.

Photo credit: Mark Bealer, Studio 66

Charlie Wardell is the Managing Editor of Offsite Builder Magazine. Photos by Zachary Davidson except where noted.