New framing machines promise to reduce labor needs in the factory, while costing less than a robotic system.

- The machine can frame the interior and exterior walls for a two-story, 2000 sq. ft. house in 60 to 90 minutes. It’s also capable of installing sheathing, cutting out window and door openings and drilling holes for electrical wires. It can even hang and tape drywall.

- The head researcher has developed a Revit add-on that will convert data from an architectural model into machine-readable instructions.

- Researchers have also built a semi-automated machine for framing walls with light-gauge steel.

Mohamed Al-Hussein is a Professor in the Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering at the Hole School of Construction Engineering at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

He and his team have developed two semi-automated framing machines — one for light wood and one for light-gauge steel — which they’re planning to commercialize. We talked with Al-Hussein about how these machines differ from what’s currently available and how they can benefit the North American construction industry.

Research Background

Al-Hussein is interested in a product approach to construction — which includes offsite manufacturing — rather than building piece-by-piece on a construction site. “Construction is a ‘man-gang’ industry,” he says. “Tradesmen tend to have a short employment span because the work is physically demanding. Women and the disabled are hardly represented among the trades.”

He believes that technology can help reduce the physical demands on workers, which has the potential to attract a wider variety of people to the industry.

He also wants to see more manufacturing in Canada. “All the consumer goods around me — my phone, my dishwasher, my car — none of them are manufactured here. We import all of them,” Al-Hussein says. “I want to educate the next generation so they can design and engage in automation-based manufacturing here.”

Currently, it’s common for offsite construction to be conventional construction under a roof, Al-Hussein says. He acknowledges the advantages of this approach — it’s better for workers and it removes weather delays. “But it doesn’t take full advantage of the indoor environment, such as the opportunity for automation, and it’s still unpredictable because it relies on human labor,” he says. “This means it’s hard to predict how long something will take and how much it’ll cost. Machines are more reliable and predictable.”

The Machine

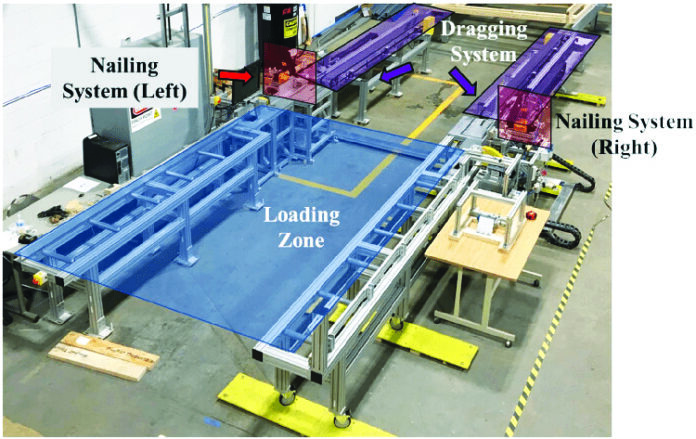

How does Al-Hussein’s machine work? After wood is manually loaded, the machine’s first function is to nail studs to the top and bottom plates, along with additional pieces needed for window and door openings.

The nailery moves in one dimension — vertically — and it fires between one and five nails, depending on the product. Then the assembly moves along to the next station. “My philosophy is to fix the tool in one location and bring the products — the studs for the wall or the joists for the floor, and so on — to the tool,” Al-Hussein says.

At the next station, sheathing is attached to the frame, openings for windows and doors are cut and holes are drilled for electrical routing. “For attaching sheathing, there’s what I call a ‘bridge’ above the wall. The bridge has multiple tools for different operations. It can nail, screw, or staple the sheathing. It can also have a router tool and a small circular saw.” It’s possible for a manufacturing facility to choose which tools they have on the bridge, depending on their processes.

“Those are the two main stations, but a third station can also install drywall, screwing it against the interior side of the frames,” Al-Hussein says. “If wanted, the machine can also handle sanding and taping the drywall, even applying a coat of primer,” he adds.

The machine can be also used to build floor systems.

There’s flexibility in the degree of automation versus the involvement of humans, e.g., for moving pieces between stations. Some factories might automate as much as possible and minimize the amount of labor needed. Others might reduce the initial expenditure and have humans perform some of the tasks and/or move the pieces between stations.

The steel-framing machine is very similar to the wood-framing machine. The functions are the same; the only difference being that the fasteners are attached in a different orientation (vertical for wood, horizontal for steel).

Is It Really New?

Al-Hussein claims that there’s nothing similar to the semi-automated steel-framing machine on the market. Semi-automated wood-framing machines are used in Germany and other European countries. But they’re designed for heavy timber that’s beyond human capacity to lift — which is why machines are necessary there, Al-Hussein explains.

“In North America, we tend to use ‘sticks’ — two-by-fours or two-by-sixes. Light wood that can be handled by one or two people.” So, the European machines would be overkill for North American needs, involving wasted expense.

Robotic arms have multiple degrees of motion, like a human hand, Al-Hussein explains. “In my semi-automated system, I use one degree of freedom at a time. And humans still feed the machine.” This contrasts with autonomous robotic systems, which can pick up materials and feed machines without human intervention.

Speed of Assembly

How quickly can the machines assemble a wall panel?

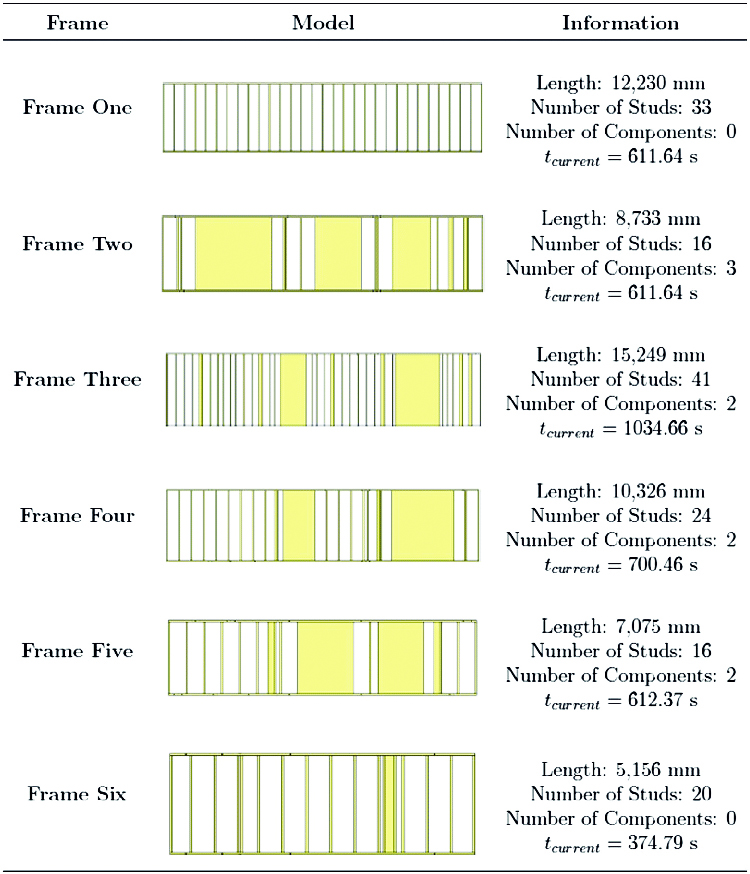

If the studs and other materials are cut to the right size and ready to put in the machine, a stud can be fastened to the top and bottom plate every five to eight seconds. “This means all the interior and exterior wall frames for a two-story, 2000 sq. ft. house can be completed in 60 to 90 minutes,” Al-Hussein says. It will take a similar amount of time to put all the sheathing on.

The time to complete a home will, of course, depend on the design — whether it has a walk-out basement, the number of interior walls, how many doors and windows it has, etc. “The entire framing process needs only one person and the machine — and maybe one or two people to help bring the materials to the machine and unload the products at the end.”

Designing for Automation

Working with automation makes the design process more demanding. “In conventional wood construction, there’s no need to invest in high-quality drawings. You can get a permit with very little information on the drawings,” Al-Hussein explains. “Framers can create a mental picture and use their expertise to build framing on-site. Product quality is driven by experience. Drafting for machines requires much more detail and precision.”

The most popular drafting software in North America is Autodesk Revit, Al-Hussein says. Although it works well for conventional construction, it’s not designed for manufacturing.

To address this shortcoming Al-Hussein says that he created a Revit add-on called Frame X. “It translates a Revit model into models of the components (walls and floors) and sub-assemblies (such as doors and frames). And then other software translates those designs into machine-readable instructions.”

Current Stage of Development

Over the years, about 70 undergraduates, as well as about 20 graduate and post-doctoral students, have worked on the design, development and prototyping of the machines. They’ve been in civil, mechanical, electrical engineering and computer science programs. Al-Hussein wants to empower the next generation to work with construction automation. “Unfortunately, at the moment, most of them don’t stay in Canada because the construction industry here isn’t ready for them,” he says.

Al-Hussein wants to change that. He’s currently devising a business plan to attract investors and is also working with the university to create a spin-off company. “The university encourages us to commercialize, to apply findings in the lab to industry.”

He’s still working out how much the machines will ultimately cost, but estimates that they’ll be significantly less expensive than European semi-automated framing machines — which aren’t even designed for the light-wood framing that’s prevalent in North America.

“These machines are tailored to the North American construction industry and would also avoid costly transatlantic shipping,” Al-Hussein says. His goal “is to make the machines affordable, so small businesses needn’t fear a heavy upfront investment.”